To say that a young Jackson Andrews couldn’t have foreseen becoming a senior leader at the Tennessee Aquarium is a tremendous understatement.

A former theater student with an associate’s degree in marine science, Andrews wasn’t even considering working for aquariums when he graduated from a university in Maine. His ambitions lay in deeper waters.

“My goal was to maybe work on a research vessel out to sea,” he says. “But there wasn’t enough research work around to do that.”

Andrews’ quest for employment took him to Florida, where he was living when a former teacher called to suggest he look into an opportunity to work for a small, family-run aquarium on Cape Cod.

Initially, he balked.

“I didn’t see the point,” he says. “I was much more interested in what marine animals were doing in the wild. If I wanted to see fish, I could just get in the ocean.”

Strange to think that, 50 years later, Andrews served on the senior leadership of the Tennessee Aquarium for more than 32 years, the last six as its vice president and chief operating officer. That influential career came to a close when he retired on March 10.

Andrews’ three decades of service encompass the entire sweep of the Aquarium’s history, beginning 15 months before the opening of the River Journey building through its growth into an internationally respected organization responsible for attracting 27 million visitors to Chattanooga.

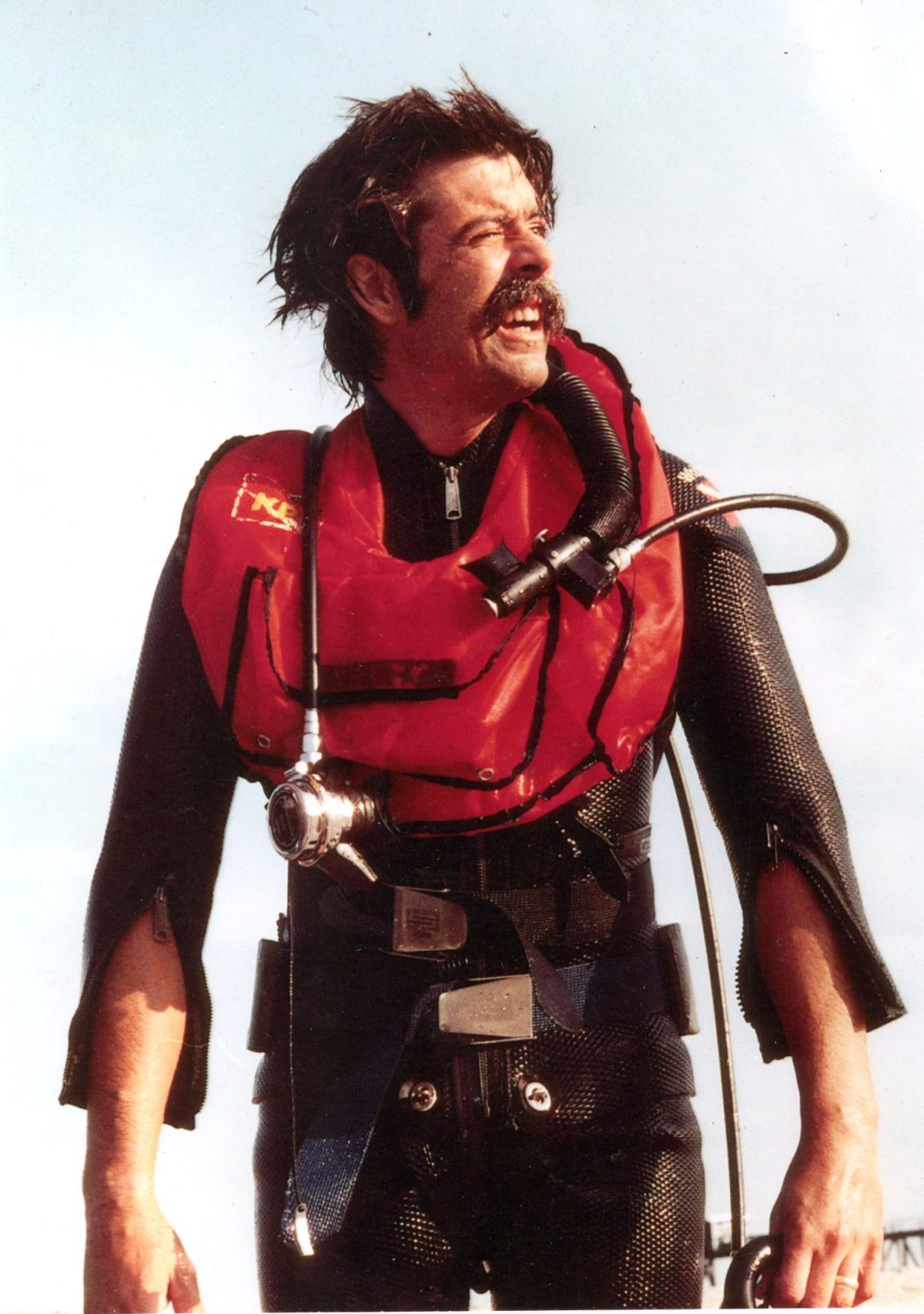

Fig. 1 (Left) A young Jackson Andrews wears dive gear after a swim in the waters of Cape Cod early in his career as an aquarist. (Right) A Gentoo Penguin swims in the Penguins' Rock gallery. Penguins were among the animals exhibited at the Cape Cod aquarium at which Jackson Andrews began his career.

A foot in the door

At the time he received his professor’s fateful call so many year ago, however, Andrews’ role as a leader in the aquarium industry was still well over the horizon. Jobless and seeking to get his foot in the door — any door — the opportunity in Cape Cod wasn’t one he could afford to ignore.

After calling the aquarium and being invited to interview in person, he asked for his sister’s help to buy a plane ticket so he could make his way to Massachusetts.

“I went there and talked to them and thought it would be a good start for me,” he says. “They called me back a few days later and said that, if I wanted it, the job was mine.”

Helping to manage and care for a diverse collection of fish, penguins and various marine mammals was an eye-opening experience that changed his opinion about the aquarium industry. Rather than viewing aquariums as a pale shadow of the “real thing,” Andrews saw in them a chance to open others’ eyes to the wonder of aquatic life.

“You could educate a lot more people about marine life at an aquarium,” he says. “I found myself saying, ‘This is pretty cool. This is something I can do here or move on to another aquarium.’”

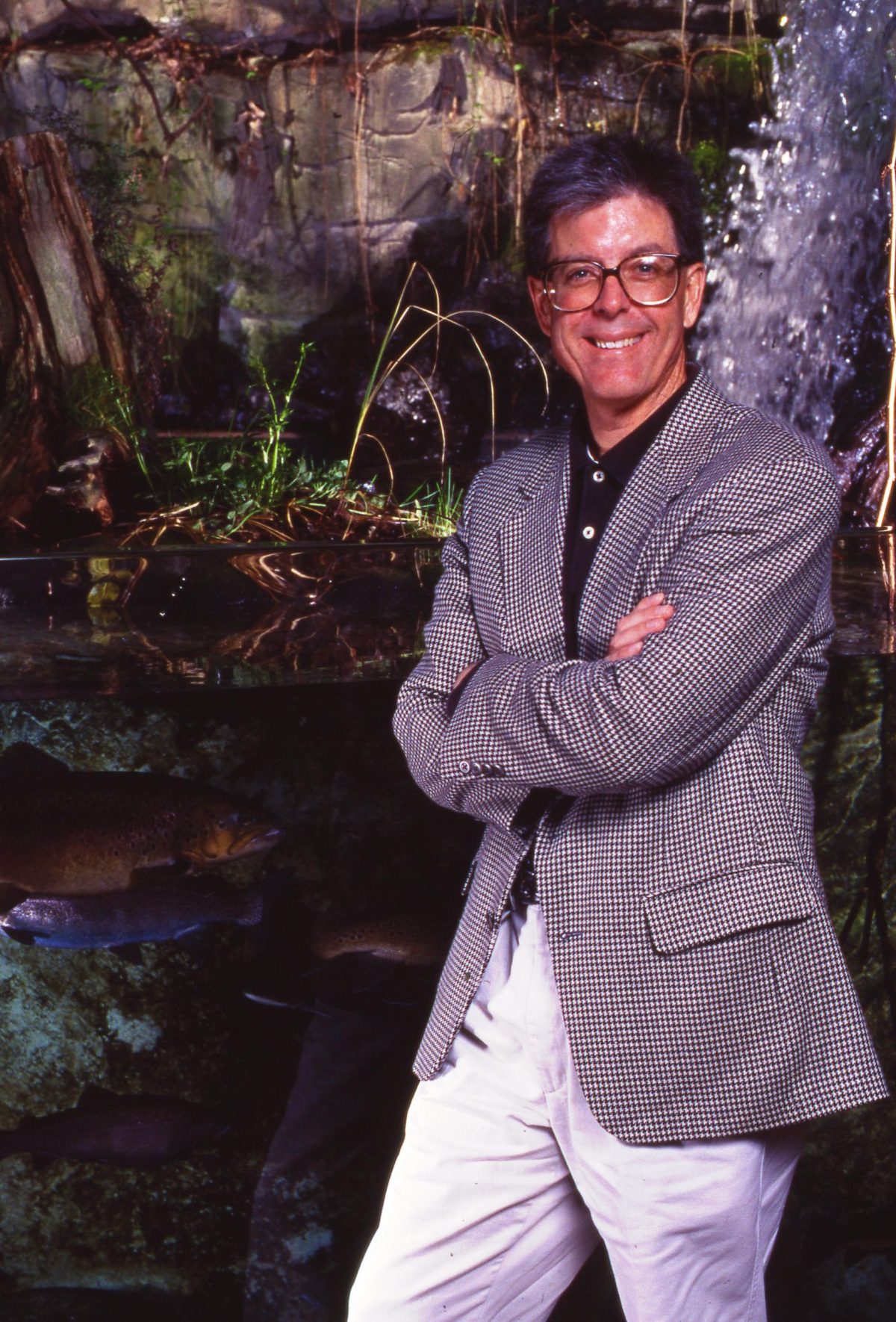

Fig. 2 (Left) Baltimore's Inner Harbor skyline, with the National Aquarium and other attractions. (Right) Jackson Andrews poses next to the Alligator Bayou exhibit in the Tennessee Aquarium. Andrews rose through the ranks at both institutions, eventually becoming the Chattanooga institution's vice president and chief operating officer.

From Baltimore to Chattanooga

Several years into his time at Cape Cod, Andrews attended a fish-care workshop at the New York Aquarium. There, he met a man who was among the leadership of the Baltimore Aquarium (now known as the National Aquarium), which was still under construction in Maryland. The two hit it off, and Andrews invited his acquaintance to pay a visit to view the exhibits for which he was responsible, including a display of needlefish of which he was especially proud.

That invitation and subsequent visit resulted in a job offer to work at the Baltimore facility. There, Andrews spent 13 years honing his skills, first as an aquarist before graduating to assistant curator and — eventually — director of husbandry.

During this time, Andrews reported to William Flynn, the facility’s deputy executive director with decades of experience in the aquarium field. In the late ’80s, Flynn was approached by representatives from Chattanooga who sought his advice on the planning and development of the Tennessee Aquarium, whose grand opening was still years away.

Eventually, they offered Flynn the role as the Chattanooga facility’s first president and CEO, which he accepted. Despite his own vast personal experience in the field, Flynn was outspoken about the importance of building a capable team as the key to an organization’s success.

“I depend on people,” he told the Chattanooga News-Free Press in a 1992 interview on the eve of the Tennessee Aquarium’s opening. “That’s what I consider management to be: getting the right people for the job in the right spot, letting them do the job and leaving them alone except when they need advice.”

When it came time to find someone to see to the care of the animals that eventually would call the Tennessee Aquarium home, he turned to Andrews, a past colleague who he considered an ideal fit for the role.

“Bill hadn’t found somebody who was a fish guy,” Andrews recalls, adding that his former director extended an invitation to visit Chattanooga to evaluate the city and consider becoming his director of husbandry and operations.

“I got back to him and said, ‘I’m really excited about this aquarium. I’d love to work here.’ The rest is history,” he laughs.

Fig. 3 Tennessee Aquarium Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Jackson Andrews speaks with Association of Zoos and Aquariums President Dan Ashe during a 2019 visit. Throughout his career, Andrews served numerous roles with AZA, including 12 years as a member of the committee responsible for evaluating zoos and aquariums seeking accreditation with the association.

Great expectations

Throughout his career, Andrews has developed a well-established reputation for being exacting and holding himself and others to an exceptionally high standard.

“There’s hardly a word he says that doesn’t speak to his desire for excellence in everything we do,” says Director of Facilities and Safety Rodney Fuller, who has worked alongside Andrews since the Aquarium’s days as an active construction site.

“That drive inspires us to do our best and to reach for higher levels of excellence. I think that’s had a very positive impact on the success of the Aquarium,” Fuller adds. “As far as what will be appealing to guests, what’s expected of animal health — he set those standards incredibly high, and I think he’s well known for that throughout the industry.”

That attention to detail and dedication to excellence has seen the Aquarium continuously meet the demanding standards necessary to achieve accreditation by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) for 30 years.

To achieve accreditation, a zoological facility is evaluated during a multi-day site visit that examines every aspect of its operation, from finances and veterinary resources to education programming, guest service and the state of its facilities. No facet of an organization is left unscrutinized.

Accreditation is a process with which Andrews is intimately familiar, having served in many capacities with AZA. His various roles include chairing the program committee, serving as a member of the ethics board and board of directors and two six-year stints on the association’s accreditation commission, which evaluates facilities seeking certification.

Fig. 4 (Left) Tennessee Aquarium Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Jackson Andrews listens while Veterinarian Dr. Chris Keller discusses preparations for an animal care procedure. (Right) Senior Animal Care Specialist Maggie Sipe feeds lettuce to Ring-tailed Lemurs. Throughout his career, Andrews emphasized that animal care and welfare were the Aquarium's top priorities.

The bottom line

When it comes to zoos and aquariums, nothing is more important than the animals’ health and welfare, Andrews says.

“We have to make sure that the care for the animals we have is top-notch,” he says. “As far as the animals go, that’s the most important thing we’ve got.”

Shortly after joining the Aquarium, Andrews sought out a local veterinarian who could oversee treatment and care for the thousands of animals for which the Aquarium was responsible. That search led him to Dr. Chris Keller, who was hired as staff veterinarian in late 1991.

Andrews’ outspoken dedication to animal welfare has defined his management of the Aquarium’s living collection, Keller says, adding that expense has never barred their shared interest in providing the highest possible standard of care.

“In the 32 years I’ve known Jackson, I’ve never gone to him with a need or a requirement for something that I thought would help us take better care of our animals and been rejected,” Dr. Keller says. “No matter how costly it was, he would find a way to do it.

“Unlike a lot of facilities, where administrators are looking at the bottom line, he always saw through that and realized that the bottom line is the animals and the rest of it would follow from that.”

Fig. 5 Then working as director of operations and husbandry, Jackson Andrews serves food to Aquarium staff members during a holiday event. As he retires, Andrews says the thing he will most is his colleagues.

Making way

From a New Englander with sea-foam dreams of manning a research vessel to a respected leader of an industry he never set out to join, Andrews looks back on his career and colleagues with no small amount of pride.

“I’ll miss the camaraderie the most, the people who work here,” he says. “The crew we have here is top-notch. Everyone who works here wants to do the best job they can and are interested in learning more. I just think this is a really nice environment.”

Having served as one of the figures responsible for seeing the Aquarium become solidly established as a respected institution, Andrews says it’s time to move on.

As important as it was for him to seize the opportunity to join the field so many years ago, Andrews says it’s equally important to make way for future generations to carry the torch and guide the Aquarium toward future successes.

“I think it’s wise of me to get out of the way and let them do it,” he says, mouth quirking into a toothy grin.

“But,” he adds, “I leave with a smile on my face.”