For more than a year, aquarists have been working on a way to minimize the Aquarium’s impact on the ocean’s fish populations by collecting eggs laid in the Secret Reef exhibit and raising the larval fish on-site rather than ordering animals taken from the wild.“Almost all saltwater fish in captivity, whether it’s at another aquarium or in your tank at home, come out of the ocean,” says Senior Aquarist Kyle McPheeters, who began working on the project with Aquarist II Tasha Esaki in January 2017. “The industry is moving to be more sustainable and asking what things we can do so we’re not having to take fish out of the ocean constantly.”

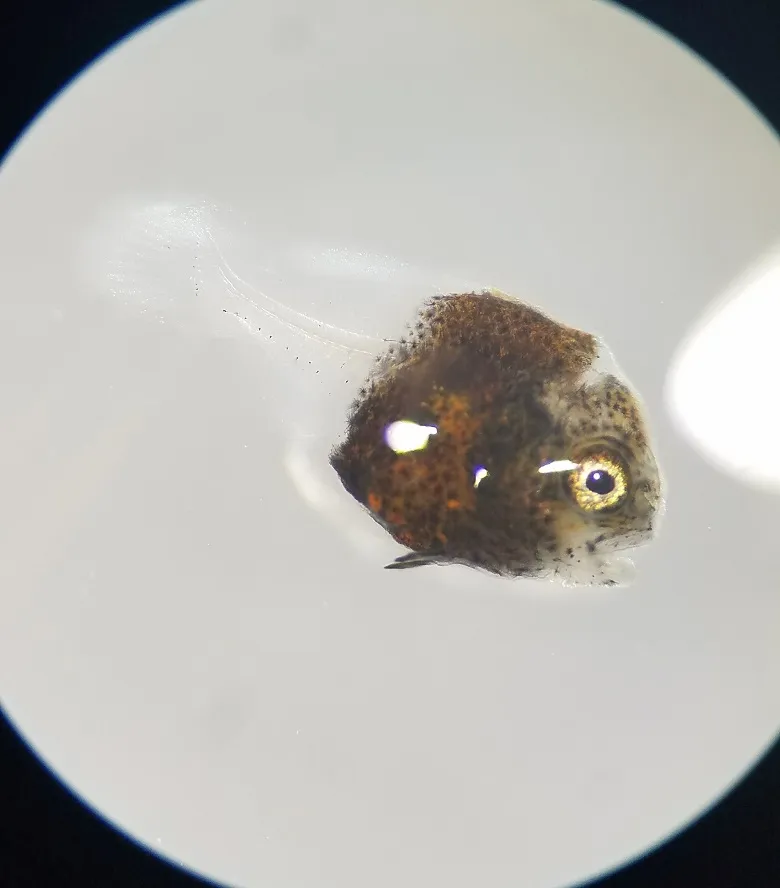

In general, newly hatched freshwater fish are larger, making them easier to raise in human care. Saltwater fish increase the survivability of their tiny offspring by reproducing in large numbers through a process called broadcast spawning, wherein adults dumping huge quantities of eggs and sperm into the water to fertilize and be carried away by the current.

Because so few institutions have managed to raise marine fish, aquarists didn’t have the benefit of literature or guides to walk them through the process. As a result, the first year of the project has been an exercise in trial and error.

The industry is moving to be more sustainable and asking what things we can do so we’re not having to take fish out of the ocean constantly.

The crucial first step was figuring out how to reliably grow live algae. In the project’s home in an alcove above the Secret Reef, one wall houses shelves filled with glass vessels of bubbling liquid. Each jar contains billions of single-celled Isochrysis algae, who darken the water from amber to mocha as their numbers increase.

Achieving a reliable source of algae was a trial, in and of itself. Air is filtered twice before reaching the containers, where it is mixed with carbon dioxide to encourage the algae to grow faster. The water is similarly purified by being bleached and de-chlorinated before cycling continuously through an ultraviolet filter.

“One of the biggest kinks with the algae culturing was not having our sterility dialed in,” Esaki says. “All the conditions for the algae need to be sterile because we don’t want anything else growing in there.”

Growing the algae solves the first of many issues with raising larval fish: they’re too small to eat most foods. Once the algae have reproduced in sufficient numbers, however, they are emptied into tubs filled with organisms called copepods. At 50-400 microns in size (0.05-0.4 millimeters), these microscopic crustaceans are just small enough for larval fish to consume.

Solving the larval fish’s diet was an important first step, but there are many other obstacles to raising them, McPheeters says.

“Even with this, a good food, we still have many factors to overcome,” he says. “Creating a stable, healthy marine environment is really what we do in every exhibit every day, but even with that and a good food source, we get stumped plenty of times.”

So far, aquarists have used a suctioning egg collector to safely collected fertilized eggs from the Secret Reef tank. But because of how many species reproduce through broadcast spawning and the similarity in appearance between the eggs of different species, it’s next to impossible to tell what species’ eggs have been collected at this stage.

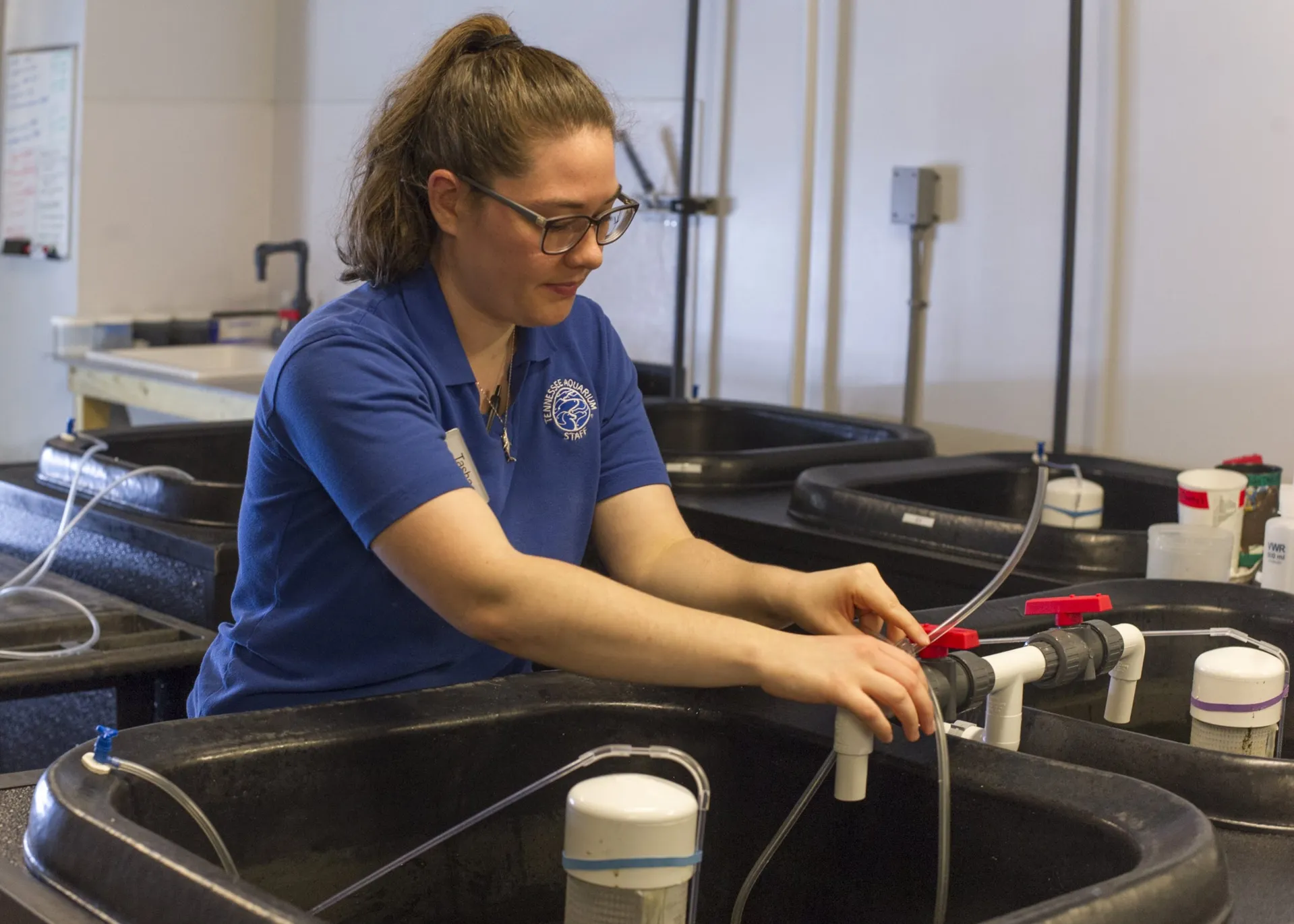

Once collected, these eggs are then relocated — carefully — into a series of six tanks in the larval fish alcove, where the conditions such as temperature, water quality and even light must be carefully controlled.

Since the start of the project, Esaki and McPheeters have collected eggs 15 times and successfully hatched several species, including Sergeant Majors, Bermuda Chubs and Atlantic Spade Fish.

There are still many questions and unresolved issues to sort out, but these baby fish represent an important in helping the aquarium industry, as a whole, to make strides towards minimizing its impact on the wild.

“This is in such a state of infancy that it’s up to us, as public aquariums, to start learning how to raise these fish,” McPheeters says. “It just hasn’t been done.”

It just hasn’t been done.