When scientists at the Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute were preparing to spawn their latest brood stock of Southern Appalachian Brook Trout, they weren’t sure what to expect.

The more than a decade-old program to restore native “Brookies” to their home waters in East Tennessee has seen incredible success in recent years. In the last two years, release classes of more than 1,000 juveniles have been returned into designated streams in the Tellico Wilderness Area of the Cherokee National Forest, where their parents originated.

The Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) determines which streams should be targeted for restoration. The program has been so successful that the agency wrapped its restoration efforts in those locations. Beginning this year and continuing through 2024, the team has shifted focus to a new area further east in the Nolichucky River system, which flows through Western North Carolina and East Tennessee.

It’s essential for the genetic health and diversity of trout populations that reintroduced juveniles are the offspring of adults from those same stream systems. This year, the shift to a new river system this year meant biologists needed to retire the Conservation Institute’s former brood stock, which are now living comfortably in the Aquarium’s Mountain Stream exhibit. This spring, a team from the Conservation Institute joined representatives from TWRA to collect new brood stock from Phillips Hollow in the northern reaches of the Cherokee National Forest.

Starting over from scratch is challenging, however, and the new brood stock meant that conservation scientists were now working with a much smaller starter population comprising fewer than a dozen adult fish.

The spawning process begins by retrieving each adult from their runs at the Conservation Institute and placing them in water with a mild anesthetic. Once sedated, each fish is weighed, measured, and quickly dried before continuing.

Drying a fish might seem counterintuitive, but it’s vital for success. Water will immediately activate the trout’s eggs, but by keeping them dry, they can work through the process of fertilizing them step by step.

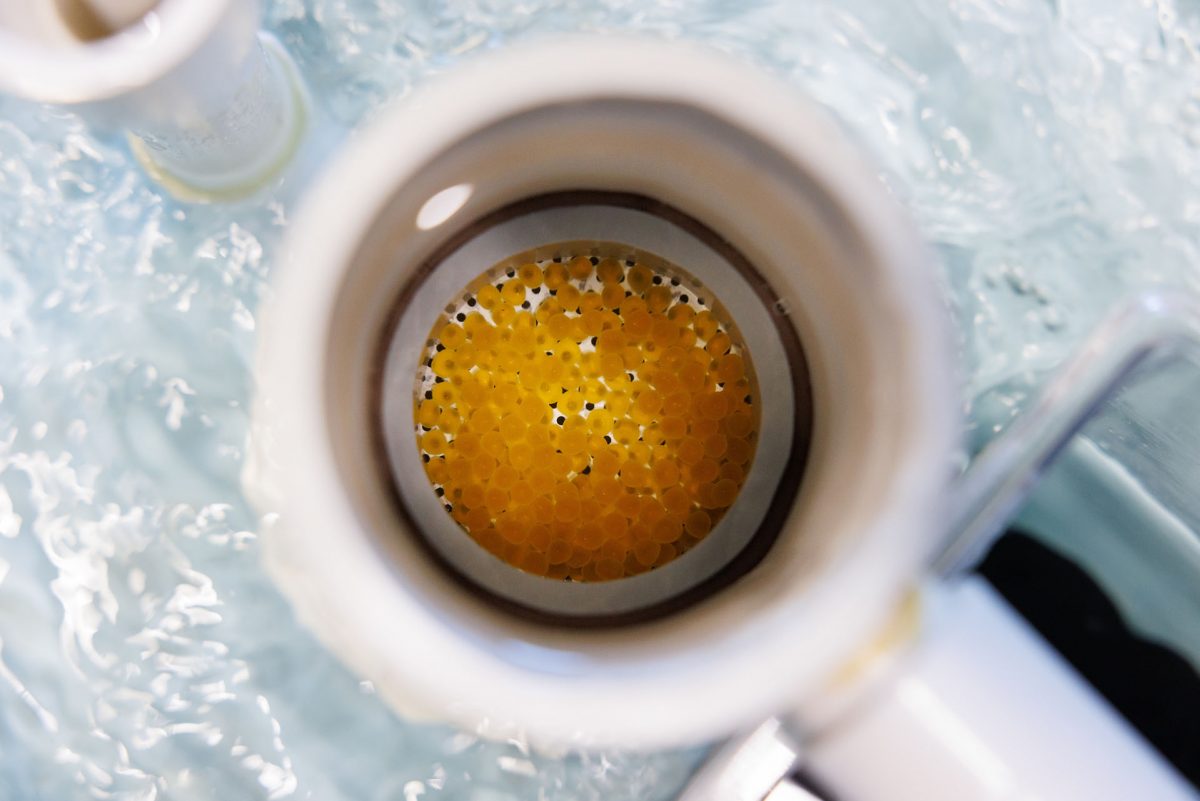

Once the fish is dry, scientists gently squeeze along its side, feeling for eggs. Once located, they can collect the eggs in a steel bowl by gently squeezing them along the side of the fish. Each female can carry dozens of these tiny golden orbs.

After they have eggs, scientists repeat the procedure with two males, gently squeezing along their sides to expel milt atop the eggs. This mixture is then stirred with a turkey feather — a traditional choice for fisheries — and sanitized through immersion in saltwater and an iodine disinfectant. Afterward, the eggs are deposited carefully in the facility’s baby trout runs inside a covered jar connected to the run’s water supply to ensure they receive adequate water flow.

Left: Eggs are gently squeezed from a female Southern Appalachian Brook Trout. Right: Fertilized eggs are kept in fast-flowing, highly oxygenated water as they mature.

There, they’ll sit in darkness as they mature, developing eyes in about a month and hatching just a few weeks later. Beginning as tiny fry, conservation scientists will raise them in these runs until they’re about two inches long. In May, scientists will transport the juvenile fish to the mountains of Northeast Tennessee and release them in Rocky Creek in the Nolichucky River system.

On the spawning day, the team began working with apprehension, but that quickly turned to success as dozens of golden orbs spilled from a female trout, marking the first major milestone for the new season and a new beginning for this breeding population.

“As a biologist, this day is very important to me,” says Reintroduction Biologist II Sarah Kate Bailey. “It’s really cool to be part of a bigger project, hopefully being able to raise these fish and then reintroduce them into an area that has so few Brook Trout left out in the wild.”