Beneath the cool fluorescent lights of a small room at the heart of the Tennessee Aquarium’s River Journey building, a team of experts in royal blue polo shirts gathers around a dusky green reptile resting quietly on the examination table.

The patient — a four-foot-long American Alligator — has been carefully sedated for the procedure, but its toothy jaws still could pose a danger to its caregivers. Working under the watchful eye of the Aquarium’s long-time veterinarian, Dr. Chris Keller, the husbandry team carefully secures a short length of PVC pipe to the alligator’s mouth to keep it open while offering safe passage for the hand of Animal Care Specialist II Kaitlyn Boteler.

Working as a team, caregivers lift the alligator from the table as Boteler inserts her hand into the alligator’s mouth, first to her wrist and eventually to her shoulder. When she reaches the stomach, she feels around for the object blocking the animal’s digestive tract.

This might seem like an unusual way to remove an obstruction, but it’s significantly less invasive than a risky surgery that would require heavier sedation, stitches and a lengthy recovery period.

Next, Senior Animal Care Specialist Jennifer Wawra, the primary caretaker of the Delta Country gallery where the alligators live, climbs onto the operating table. She carefully lifts the reptile even higher, angling his head downward to allow gravity to assist with the retrieval.

Finally, Boteler secures the object and pulls it out to a chorus of raucous cheers. No one watching this unusual spectacle take place is as excited as Keller, who is practically giddy at the successful outcome.

Keller has offered his veterinary expertise to the Aquarium throughout its 30 years on the waterfront. Finding innovative — occasionally unorthodox — solutions to complex situations like an alligator’s obstructed digestive tract speaks to a philosophy of care that relies on working in concert with the husbandry specialists who see his furry, scaly or feathered patients every single day.

Left: Dr. Chris Keller holds a turtle during the Aquarium's early years. Right: Keller treats a sick reptile.

Learn from others

Keller’s career seeing to the needs of the Aquarium’s more than 12,000 animals representing more than 600 species began before the facility opened its doors.

Having recently moved to the Chattanooga area, with a wife and newborn, Keller had just started his own practice in 1991 and was looking for work that could offer variety. He previously had served as a volunteer at Knoxville Zoo and a graduate student working as a wildlife biologist trapping, sedating and collaring Black bears in the Great Smoky Mountains. This experience set him apart since there were few opportunities at the time for veterinary students to learn exotic animal medicine.

When Keller arrived to interview for the staff veterinary position, the entire River Journey building was a construction zone save for a single room in the basement, a kind of staging area for animals waiting to be moved into exhibits as they were completed.

“I walked in the construction trailer, they gave me a hard hat and had me sign in,” Keller recalls of this first visit. “I felt just like Bob the Builder.”

After a working interview with the Aquarium’s administration and curator, Keller was offered the job and started in October of 1991.

At first, the job was like being a farm veterinarian. Keller would provide specialized care for the aquarium’s collection three times a week and then bill them for his time. As time passed, Dr. Keller became more and more involved with the day-to-day care of the animals and slowly began to feel like a permanent fixture.

“I didn’t want to come only when something was happening,” Keller says. “I wanted accessibility. I wanted to get to know the staff, so I could be a resource to help steer and direct care.”

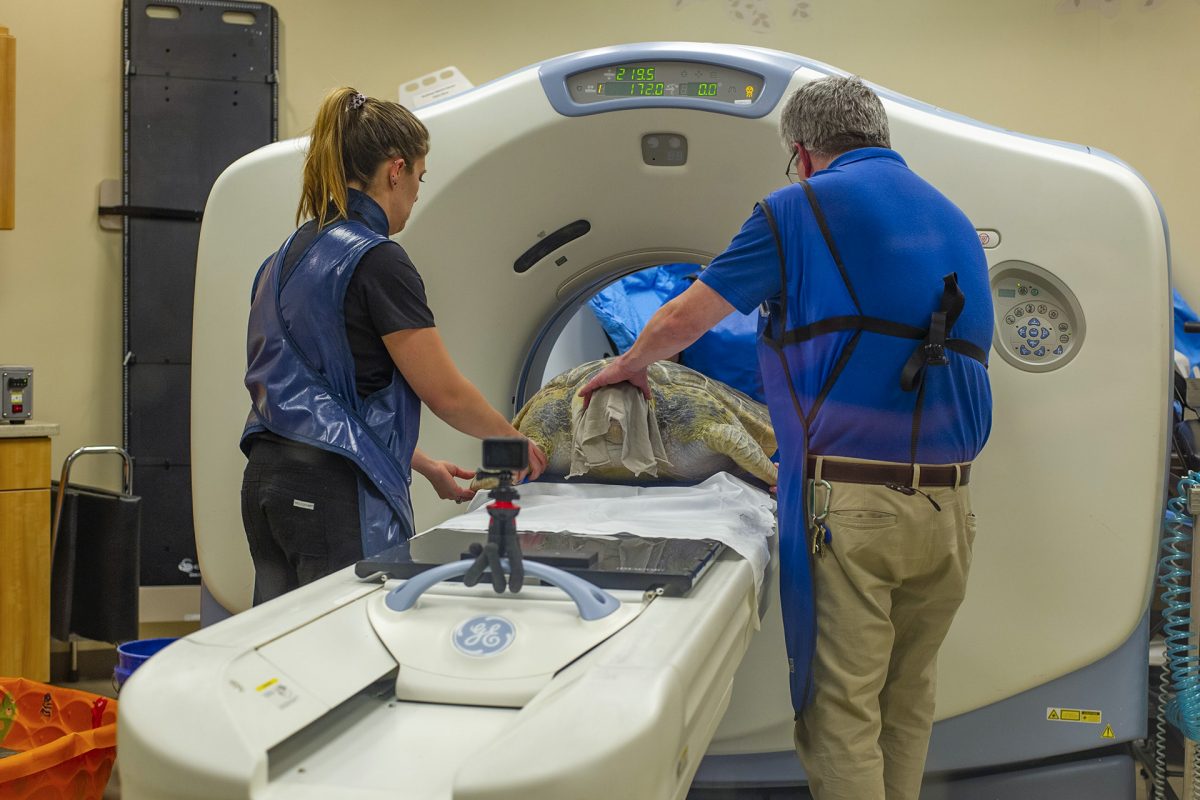

Left: Keller assists with the MRI of Green Sea Turtle Oscar. Right: Keller performs a physical exam on a Ring-tailed Lemur.

When Keller began practicing, he says, few veterinary schools offered courses in aquatic animal medicine, especially focused on care for fish. In contrast, fisheries biologists were well-trained in natural history, fish husbandry and hatcheries science. Consequently, veterinarians were not always sought out by aquarists when issues arose.

Gradually, that attitude began to change as Keller worked alongside the Aquarium’s aquarists to find creative solutions to medical problems. Ultimately, he says, it was crucial to set territories aside and work together to do what was best for the animals.

The benefits of this collaborative approach were numerous. Working with the Aquarium’s fish experts, Keller found that pooling their knowledge and sharing ideas was far more effective than handing down unilateral diagnoses and treatment procedures. This philosophy resulted in better outcomes for patients, he says.

“I think there were a handful of pioneering fish veterinarians who weren’t willing to listen to what other people could teach them,” Keller says. “I was always — hopefully — the opposite of that.”

His first fish surgery was one of early bellwethers of this collaborative method. Fatty deposits had accumulated on the cornea of a fish’s eye, severely impacting its ability to see, and the care team needed to come up with a solution to save its life.

These days, there is plenty of literature available to plan a course of action to address these kinds of issues, but at the time, Keller could find no examples of anyone performing surgery of this type on a fish’s eye before.

From anesthesia to the removal of the accumulated fat deposits, the procedure was daunting. By pooling their knowledge and using common-sense comparisons between fish and other animals, however, Keller and the rest of the husbandry team successfully restored the fish’s vision. The animal, which had not eaten in weeks, immediately resumed normal behavior the following day.

“We were able to accomplish that with people who were always willing to try and never say ‘no’ to creative ideas,” Keller says.

Be a sponge

Keller’s pathway to becoming an aquarium veterinarian looked a little different than the route most current vet students take.

There were few veterinarians specializing in exotic animal medicine when he started out. Today, veterinary students often know the type of vet they’d like to be even before they begin vet school. They aggressively pursue zoo and aquarium medicine because the field has become extremely competitive. Today’s budding veterinarians have access to new and relatively recent resources — like the American Association of Fish Veterinarians (AAFV) and the World Aquatic Veterinary Medical Association (WAVMA) — that didn’t exist or were in their infancy when Keller’s career began.

“I think, more and more, one of the things that stands out about my work is that the field is generalized,” Keller says.

Keller believes his wide-ranging experience in both exotic and domestic animal care gives him a lot to offer to the next generation of veterinarians. His desire to give back to the profession eventually saw the creation of a series of veterinary externships offered at the Aquarium to help aspiring veterinary students interested in pursuing exotic animal medicine.

Students involved in the program shadow Keller and a husbandry team for two weeks, during which they learn about the care involved in nearly every aspect of life at the Aquarium. Through it all, Keller hopes to impart that there’s always more to learn, even after the initials “DVM” (Doctor of Veterinary Medicine) are added to their title.

“What I insist on telling everybody who comes out of veterinary schools is that everybody around you has skills and knowledge and ability. You should be willing to listen and not be above learning from people who aren’t veterinarians.”

After all, he says, veterinary medicine as a profession has only existed for a few hundred years.

Animals have a remarkable ability to heal on their own in the right environment and with a high standard of care. Introducing stress by handling a wild animal unnecessarily can sometimes do more harm than good. (Like, for example, helping an alligator who made a poor snacking choice.)

“There’s an inevitable reduction of an animal’s immunological response and physiological functions when they’re stressed,” Keller says. “You have to balance your decision to intervene against whether treatment will do enough good to overcome that.”

Young veterinarians need to learn that it isn’t always necessary to perform an invasive and stressful procedure just because they can and to remember animal care is more than just test results and cookbook medicine, Keller says.

The standout moments in Keller’s 30-year career — the cases he’ll remember long after he’s retired — are the ones where he knows only the care team at the Tennessee Aquarium could have succeeded.

“There are so many situations where I know that we handled a medical issue or an animal’s debilitating condition better than anyone else could have, and it’s because we cooperate,” he says. “It’s great to have everybody pulling on the rope in the same direction.”

Keller listens to a Macaroni Penguin's heart and lungs during a routine physical.