Kermit the Frog famously said “It’s not easy being green,” but for one of nature’s hardest-luck stories, you need only look at sea turtles.

After breaking through the safety of their eggs and leaving the nest, sea turtle hatchlings face a fraught sprint to the water under the hungry gaze of Ghost Crabs, Sea Gulls, Raccoons and a host of other predators.

Assuming they make it to the surf and bulk up for a few years, adult sea turtles have few natural predators to fear. Only about one hatchling in 1,000 actually makes it to adulthood, but for the few that beat those long odds, Mother Nature cuts them a bit of a break.

Humans, on the other hand? They make it so sea turtles hardly dare to breathe, says Senior Aquarist Jake Steventon.

“Sea turtles don’t sleep all night like we do,” Steventon says. “They have to hold their breath the whole time, so they’ll sleep for an hour or so. When they wake up, they come up, hang out at the surface, float around for a while and get several good breaths.”

And that’s when they’re in the greatest danger, he adds.

“When they’re at the surface between naps, they’re vulnerable to boaters who probably don’t see them until it’s too late. Boat propellers can tear up a sea turtle’s shell pretty badly.”

In Florida, 20 to 30 percent of stranded sea turtles are reported to have been struck by boats, according to statistics from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. When they aren’t fatal, boat strikes crack turtles’ shells and cause injuries that can lead to nerve damage or necessitate the amputation of limbs.

Fig. 1 Oscar, a young rescued Green Sea Turtle, shortly after arriving at the Tennessee Aquarium

In May 2003, a young Green Sea Turtle was hit by a boat off the Florida coast. This incident left him with a deep cut through the rear and right side of his shell and removed about a third of his left rear flipper. (His right rear flipper was already missing due to an older, healed injury and was likely the result of a predator strike.)

After his run-in, the little turtle’s chances of survival were further diminished by the deep cuts through the side of his shell by the boat propeller. By the time he was rescued by fishermen off the coast of Daytona Beach, Florida, this wound had filled with silt and debris and exposed his lung, which expanded outside his shell with every breath.

The fishermen delivered the injured turtle to the Marine Science Center in Ponce Inlet, Florida. There, care specialists worked to address his injuries, waiting between breaths to carefully sew up the cut whenever his lung wasn’t exposed.

When he arrived at the Marine Science Center, the little turtle was about the size of a dinner plate and was covered in a thick coat of green algae. In honor of his resemblance to Sesame Street’s famous grouch, the center’s staff dubbed him “Oscar.”

“BUBBLE BUTT”

Under the Science Center’s care, Oscar recovered from his injuries but was considered non-releasable due to his mangled flippers and a pocket of air in his shell that increased his buoyancy, making it difficult to swim. This air-filled cavity caused the back of Oscar’s shell to rise above his head, a condition commonly referred to as “bubble butt syndrome.”

Fig. 2 Aquarium staff caring for Oscar behind the scenes in 2005

“That’s really common in boat-strike turtles,” Steventon says. “In some cases, ‘bubble butt’ can be very problematic for turtles. It can leave them stuck at the surface and unable to dive down to get to their food.”

With no prospects for survival in the wild, it came to humans to provide a home for Oscar. In 2005, he made the journey from Florida to Chattanooga to take up residence at the Tennessee Aquarium.

When he was introduced to the (now-closed) Gulf of Mexico exhibit in the River Journey building, Oscar’s ability to move through the water astonished Aquarium staff and visitors. Despite his injured flippers, his awkward posture in the water and the deep notches on his back and right side, the little turtle relied on his strong front flippers to navigate with remarkable agility.

Fig. 3 Oscar being introduced to the Aquarium's former Gulf of Mexico exhibit in 2005 (left) and swimming at the surface of the Secret Reef tank in 2013 (right)

Fifteen years after his arrival — and now living in the Ocean Journey building’s Secret Reef exhibit — Oscar has become an Aquarium icon and a favorite of guests. Not only is he an excellent ambassador for his species, but millions of visitors have been inspired by the story of his overcoming the odds and thriving, despite his physical appearance.

“He’s a very charismatic animal, and there are different reasons why he’s special to different people,” Steventon says. “Some people like to see him because they can relate through having disabilities of their own. They see him, and it’s like, ‘Oh, we’re the same!’ I’ve heard so many different stories of people who connect with him in different ways and for different reasons.”

BACK AGAIN

Even though he survived his initial run-in with the boat, Oscar now faces a new challenge brought about by the injuries left in its wake.

In July 2019, aquarists noticed increased aggression against Oscar by the Aquarium’s other — much larger — Green Sea Turtle, Stewie. Stewie’s harassment caused an injury to Oscar’s front left flipper. Combined with his lifelong struggle with over-buoyancy, this limited Oscar’s ability to dive and avoid his tank mate.

To give him time to recuperate and for staff to attempt physical therapy to restore the use of the flipper, Oscar was relocated from the Secret Reef into a nearby acclimation pool. Before he could return, the Aquarium’s veterinary team knew they needed to address Oscar’s mobility issues.

To find a solution, they needed to get a closer look at the problem, but in a bit of herpetological irony, the same thick shells that protect sea turtles from injury can hamper veterinary efforts to diagnose them. Traditional tools like ultrasounds can’t penetrate the shell’s thick layers of keratin (the same protein found in hair and fingernails), which can make imaging internal injuries difficult.

Faced with the conundrum of how to assess an injury they couldn’t see, Aquarium staff sought specialized help. Oscar’s pluck and indomitable spirit have endeared him to many in the Chattanooga community, however, and news of his latest struggle resulted in outpourings of assistance from some unexpected sources.

A MOST UNUSUAL PATIENT

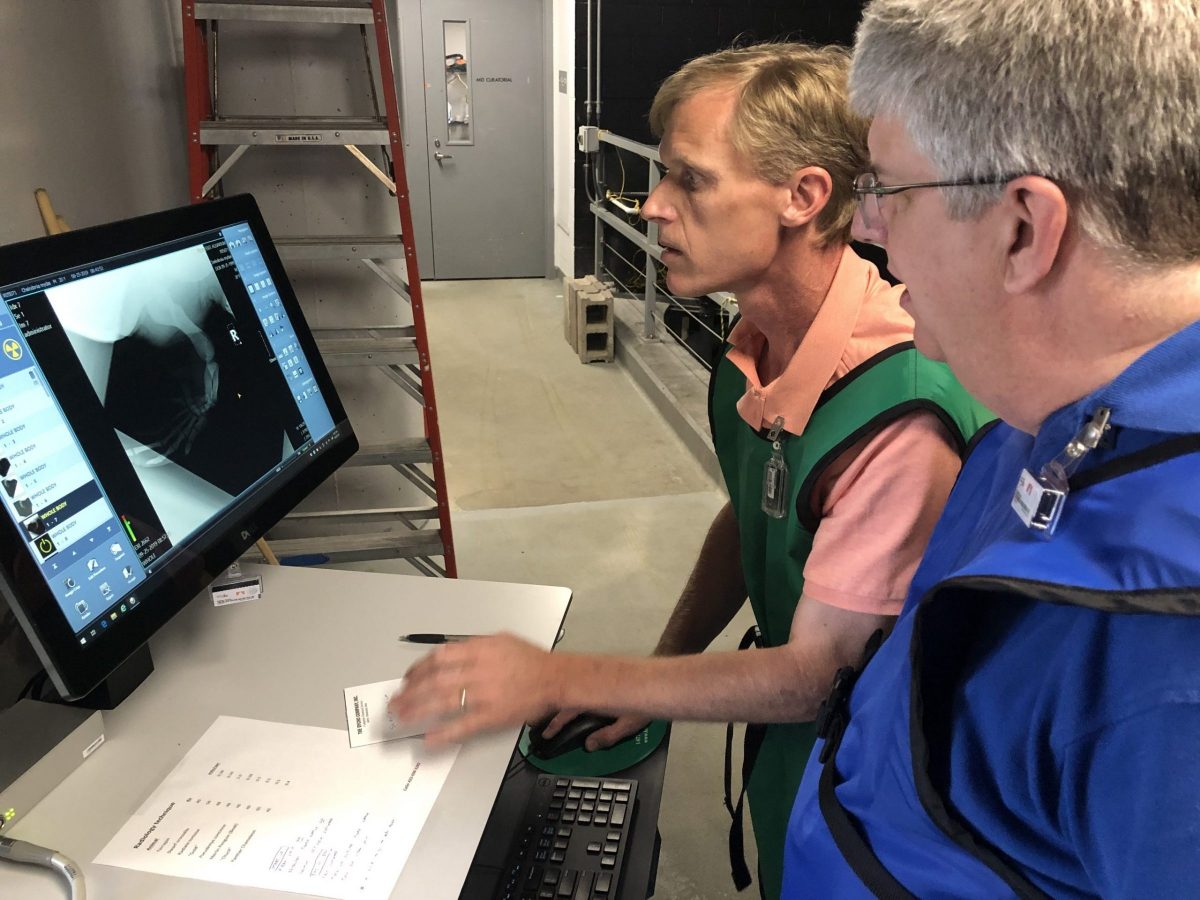

In September, Kelley X-Ray, a Chattanooga-based medical equipment company, offered the use of one of their portable x-ray machines. Colin Kelley Jr., the company’s president, brought the equipment to the Aquarium to perform scans of Oscar’s flipper and carapace (shell). Those images were shared with other sea turtle experts, but no definitive source of the injuries was identified.

Fig. 4 Despite Oscar consistently overcoming challenges his entire life, Steventon says he has been especially moved by the outpouring of assistance to help the puckish sea turtle through this latest ordeal. “My first priority is thinking about getting him through what we’re doing,” he says. “But when I reflect back on how so many people have bent over backwards to help us out and brought their equipment here, it’s just amazing how people have been willing to help out.”

Following the inconclusive x-ray, nearby CHI Memorial Hospital invited the Aquarium to use a computerized tomography scanner housed in the Rees Skillern Cancer Institute. Unlike an ultrasound, a CT scan can penetrate sea turtle shells and offered a better chance to assess Oscar’s condition.

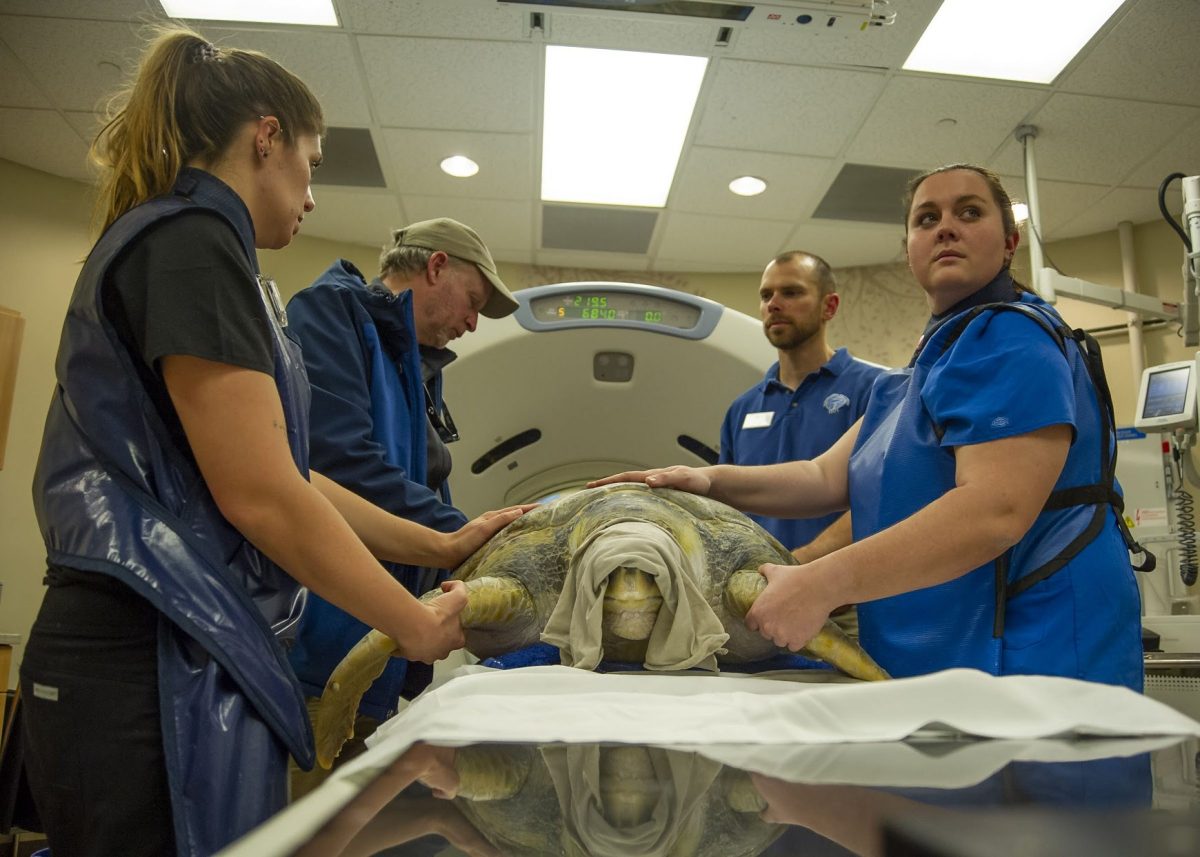

In December, a team of animal care specialists carefully relocated Oscar from the Secret Reef into a van for his trip to the hospital. After a short — extraordinarily careful — drive, the Aquarium team was met by CHI Memorial’s CT technicians and several diagnosticians, who were given the unique opportunity to lend their expertise to the care of a patient unlike any they’d ever seen before.

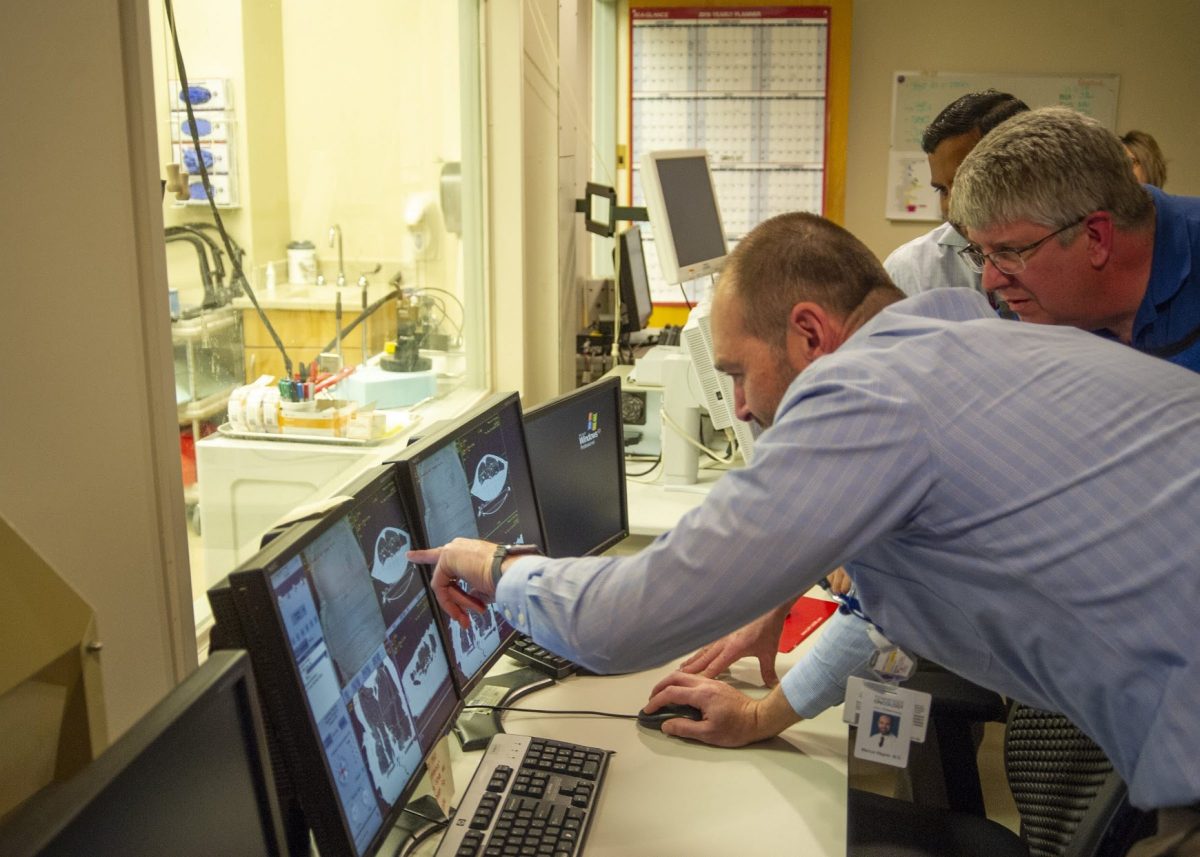

Donning protective aprons, hospital staff members and the Aquarium veterinary team remained with Oscar during his procedure. With hands on his shell and a damp towel over his head, those in attendance helped keep Oscar still as the sample table slid into the barrel-like scanner, the only one nearby that was wide enough to accommodate his broad bulk. In an adjoining diagnostic room, the results of the scan displayed in real-time on a series of monitors.

Fig. 5 Aquarist Jake Steventon and staff loading Oscar into a van (top left), CHI Memorial and Aquarium team members with Oscar in a CT machine (top right), Aquarium Veterinarian Dr. Chris Keller reviewing scans with CHI Memorial staff (bottom)

Despite the dramatic differences between sea turtle and human anatomy, the CT scan found evidence suggesting the injuries Oscar sustained early in life from his boat strike were indeed causing his new, unexpected complications. A large cavity on the left side of his shell was steadily filling with air and wasn’t being expelled, further increasing his buoyancy and preventing him from diving.

“The way Oscar rests, his posture in the water, is abnormal for sea turtles,” says Aquarium Veterinarian Dr. Chris Keller. “With his hind end sticking up, literally out of the surface of the water, and his head down the way it is, it makes it more cumbersome when he tries to swim and dive.”

Because this air leak significantly affected Oscar’s quality of life, Keller determined that an endoscopic visualization of the structure inside Oscar by a specialist was the only way to determine its source and address it. He sent the CT results to other veterinarians along the East Coast and was contacted by Dr. Shane Boylan, a renowned expert in sea turtle care at the South Carolina Aquarium.

‘MAKING THEIR LIVES BETTER’

Every year, the South Carolina Aquarium’s Sea Turtle Care Center treats an average of 60 sea turtles. About half, like Oscar, are the victims of human-made interactions, such as boat strikes, ingesting fish hooks and monofilament fishing line or being sucked up by dredges.

Many of the turtles treated by the Sea Turtle Care Center can be returned to the wild, but some that have suffered especially traumatic injuries like Oscar’s remain in human care. There, they continue to fulfill a vital role as ambassadors for other sea turtles and to serve as cautionary tales of how human interaction can impact marine life, Boylan says.

“Turtles are really interesting animals, and people just attach to them,” he explains. “I know I did as a kid. Every time I saw one hit on the side of the road, I wanted to fix it. That was as a six-year-old. As a 45-year-old, I’m trying to do the same thing; I’m trying to make their lives better.”

When he received Keller’s request for assistance, Boylan offered to drive more than 400 miles from Charleston in a car laden with highly specialized medical equipment to assist in diagnosing — and possibly treating — Oscar.

“This is why I became a veterinarian,” Boylan says. “If you’ve got a sick animal and ask for my help, I’ll come if I have the time. I’ve got expertise in this area — we’ve fixed several ruptured lungs in the past — so this is an area where I can lend some assistance.

“Oscar’s condition is the result of a boat strike, a human interaction, so we need to make up for the damage that we’ve done.”

THE PROCEDURE

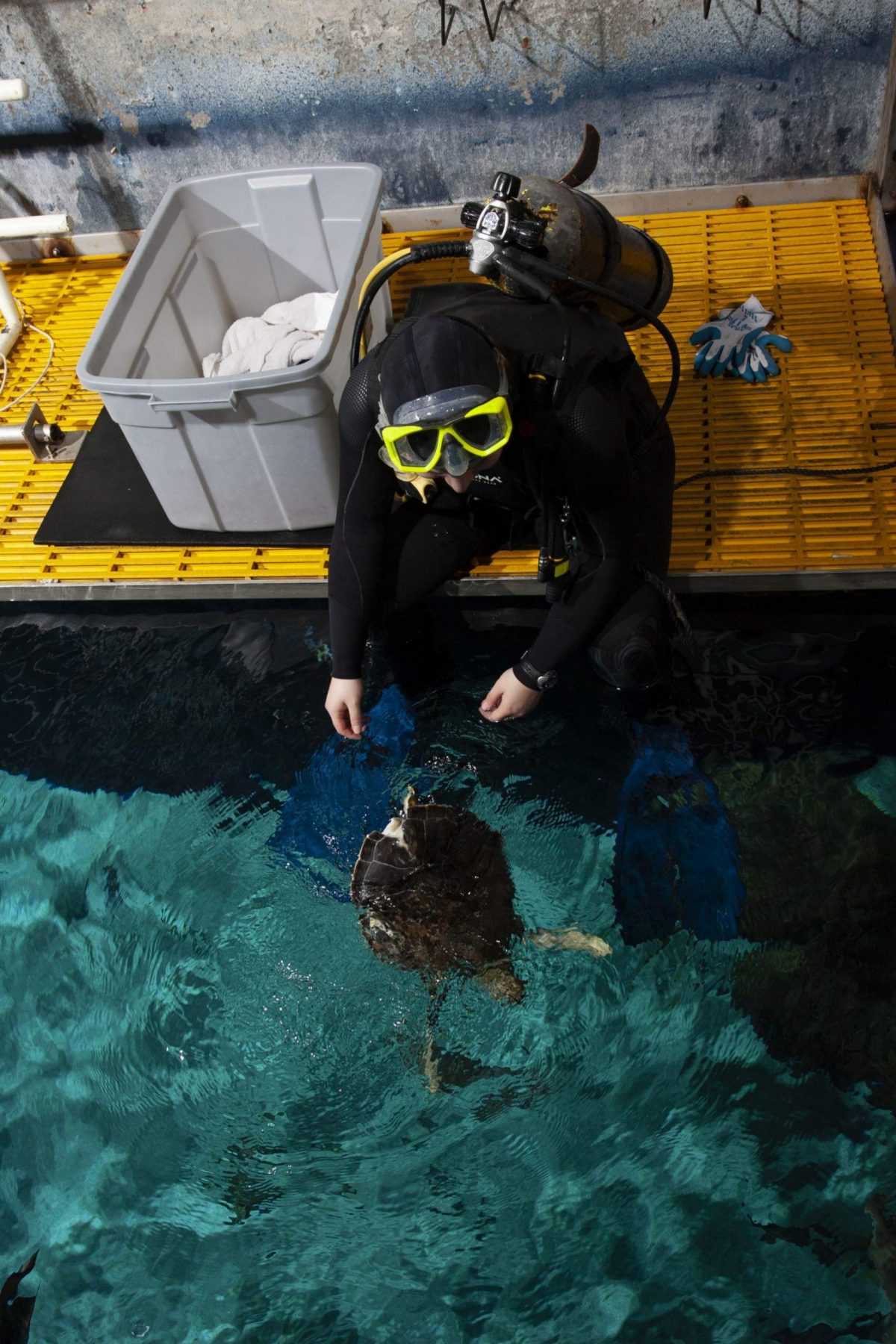

Now much larger than a dinner plate and tipping the scales at 166 pounds, moving Oscar is a highly orchestrated maneuver. The morning after Boylan arrived, Steventon and Manager of Dive Operations Mark Craven entered the recuperative pool where Oscar is temporarily housed to guide him onto a stretcher. Using a ceiling-mounted winch, the stretcher was raised so staff could gently move Oscar onto the operating table to be placed under general anesthesia.

Fig. 6 Curator of Fishes Matt Hamilton and Aquarist Jake Steventon wait with Oscar before the procedure begins (left), South Carolina Aquarium Staff Veterinarian Dr. Shane Boylan and staff viewing screen during a sea turtle bronchoscopy (right)

With their patient’s heart rate and breathing closely monitored, Keller and Boylan performed a pair of procedures to get a better look inside Oscar in hopes of determining the source of the air leak.

The four-hour examination began when Boylan fed a long bronchoscope equipped with a camera down Oscar’s windpipe to view his lungs. This tool is specifically designed to provide clear imagery deep within a patient’s respiratory passageways. Despite close scrutiny, the bronchoscopy found no signs of damaged tissue or tears that would explain the leak.

Next, Oscar was lifted onto his side, and Boylan made a small incision through the coelomic wall into the main body cavity housing his lungs, digestive tract and other internal organs. After clearing a path through Oscar’s layers of fat and muscle, Boylan began his examination using a rigid endoscope equipped with a camera.

Fig. 7 Aquarium staff surround an operating table as South Carolina Aquarium Veterinarian Dr. Shane Boylan performs a sea turtle endoscopy

Almost immediately, he found a large bulla, an air-filled sac attached to Oscar’s lung. These sacs can remain inflated even after the lung has expelled a breath and are not uncommon in turtles that have been injured by a dredge, shark attack or, in Oscar’s case, a boat strike.

“In most cases, though, they’re very, very new and acute, so in a relative sense, they’re much easier to repair,” Keller says. “You can find them and wall them off more easily.”

In many cases, bullae are small, but Boylan estimated Oscar’s had grown to the size of a large zucchini, occupying much of the space on the side of his body cavity and significantly increasing his buoyancy.

“Because Oscar’s bulla has probably been in existence from when he first suffered his original injury, it’s difficult to break down all the membranes and scar tissues associated with the original injury,” Keller says. “For whatever reason, it’s just now become much more significant and causing him more problems as he gets larger.”

THE LATEST CHALLENGE

Using a syringe, Boylan pierced the bulla and removed the entrapped air. Having identified the cause of the over-buoyancy, he then set out to find the source of the leak, the passage through which air was communicated from Oscar’s lung into the bulla. Even after a thorough examination of the lung’s exterior, however, no rent or tear could be found.

Despite offering no “cure” to Oscar’s condition, Boylan and Keller say the simple act of identifying the problem may improve his quality of life.

“By doing this surgery, alleviating some of the air-filled sacs in there and restructuring some of the tissue, Oscar’s condition might improve,” Keller says. “But it may also require additional diagnostic testing and procedures.”

After closing the incision and cleaning the surgical site, Boylan eased his patient off anesthesia. As the minutes passed and Oscar slowly reawakened, Steventon stood at his side, gently stroking his hand across the shell just inches away from the triangular notch left behind by the boat propeller.

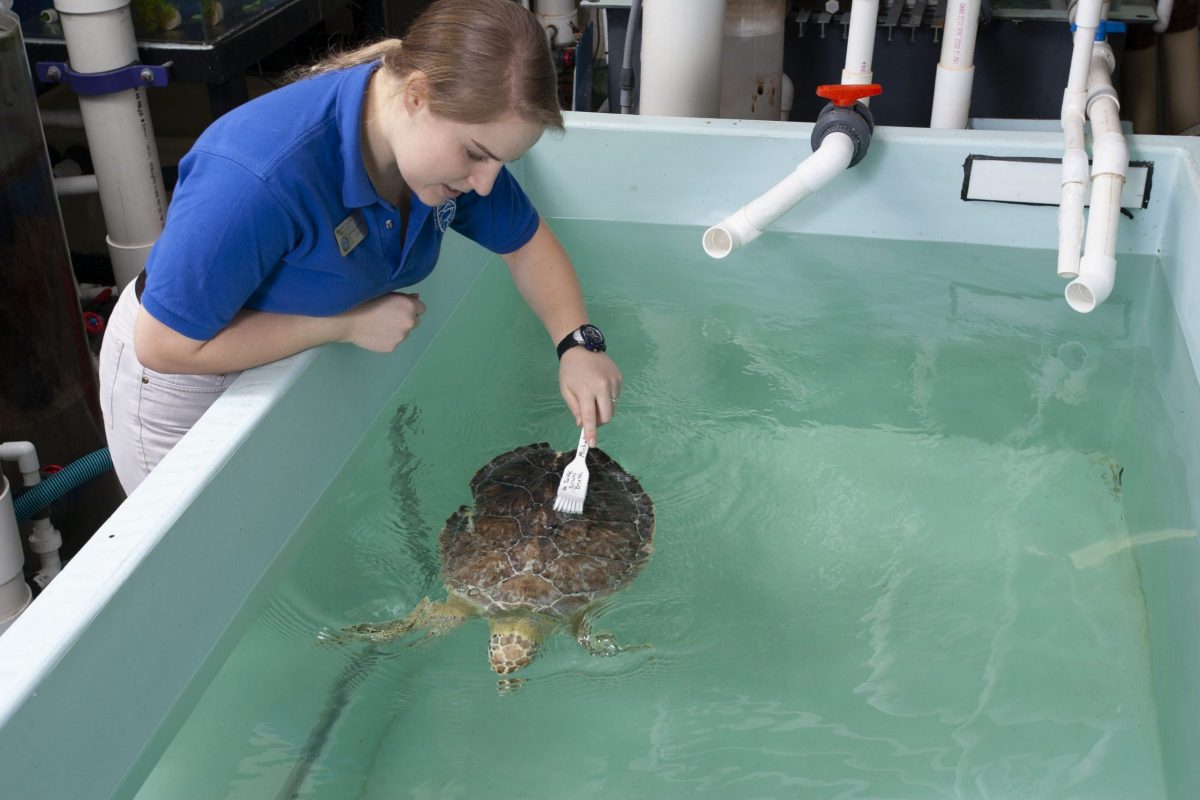

Fig. 8 Aquarist Jake Steventon and Oscar during a feeding session in an acclimation pool near the Aquarium's Secret Reef exhibit

Despite Oscar consistently overcoming challenges his entire life, Steventon says he has been especially moved by the outpouring of assistance to help the puckish sea turtle through this latest ordeal.

“My first priority is thinking about getting him through what we’re doing,” he says. “But when I reflect back on how so many people have bent over backwards to help us out and brought their equipment here, it’s just amazing how people have been willing to help out.”