When a domestic cat or dog becomes ill, the process of getting them veterinary care is usually straightforward.

A few treats and a leash or a carrier are typically all it takes to get them safely to the vet’s office. While they may not always be the most cooperative patients, the process doesn’t often come with significant risks to the animal, their owners, or the veterinary team.

It’s not so simple when your patient is a 150-pound shark.

Sandbar Sharks are fast, powerful predators with significant muscle mass to power themselves through the water. Their size and strength alone make them difficult to handle, never mind the teeth that people tend to fixate on. While not inherently dangerous or aggressive animals — they’re generally docile and prefer to be left alone by humans – Sandbar Sharks are strong enough to inadvertently cause injury during the rare times when they need to be relocated to receive treatment.

So, when aquarists discovered a suspicious mass on the anal fin of the youngest male Sandbar Shark in the Aquarium’s 618,000-gallon Secret Reef exhibit, they knew it would take a team effort to get the animal the care it needed.

The first step was observation. Any veterinary procedure can be stressful for an animal, and sometimes, the stress can be worse than the cure. Caregivers needed to be certain that intervention was required, so they watched and waited.

What began as a small section of upraised tissue on the fin grew larger and, ultimately, broke through the skin as a fibrous mass. At that point, Aquarium Veterinarian Dr. Chris Keller decided removal of the tissue – and a biopsy for analysis – was necessary to ensure the continued health of the shark.

Accomplishing that feat last week required a team from three different Aquarium departments: husbandry, veterinary and operations. They began during feeding time, using a fish attached to the end of a pole to lead the shark into a smaller acclimation pool (the “hospital pool”) adjoining the Secret Reef. This annex can be closed off from the rest of the Reef, allowing animals to be more easily observed or to be treated with greater ease.

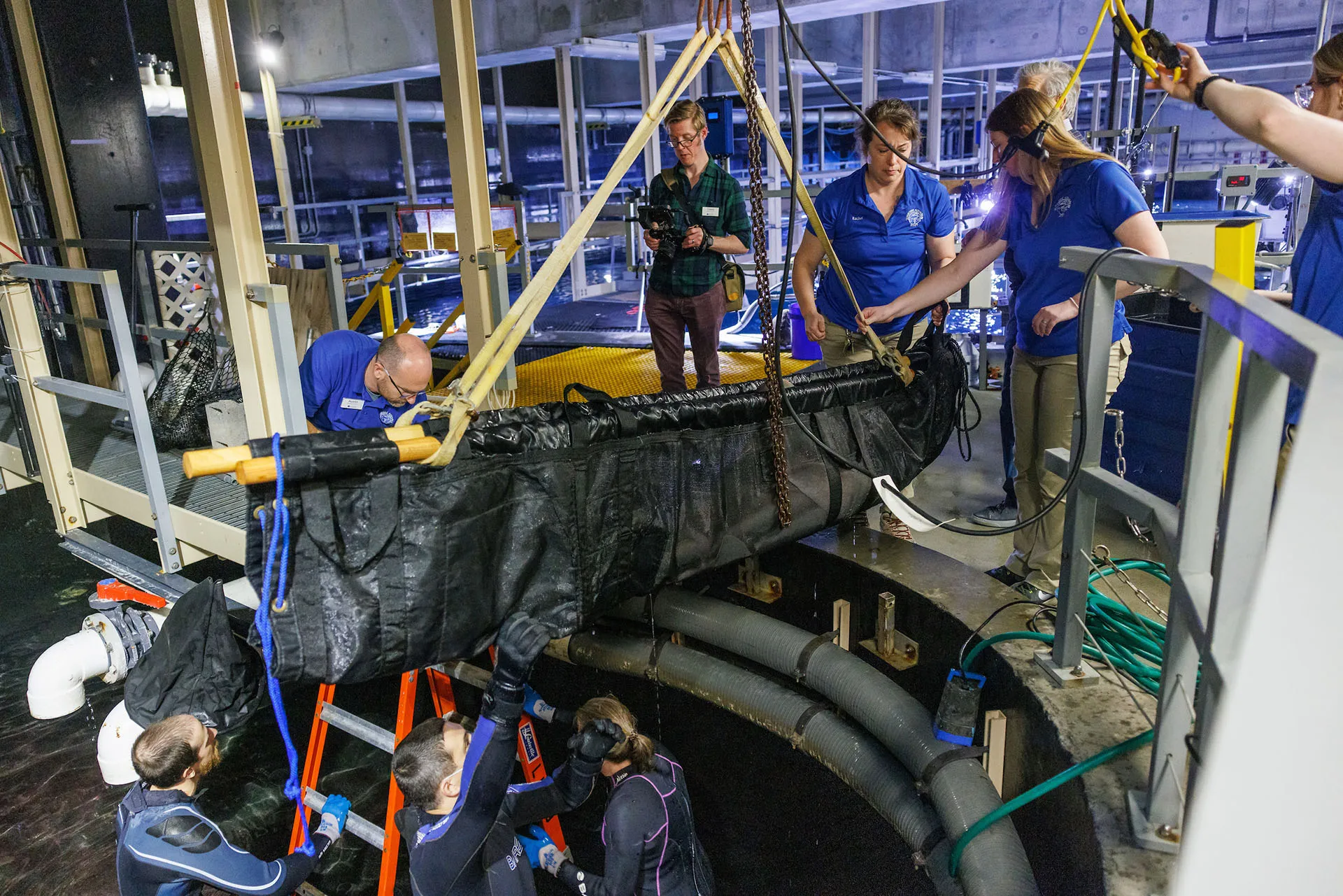

Next, operators lowered the water level in the pool until it was about knee-high. The lowered water level slows the shark’s movement while also allowing a team of wetsuit-clad aquarists to guide it into a canvas stretcher while minimizing stress to the animal.

Once safely inside the stretcher and calmed with a hood drawn over its head, the shark was raised out of the water with an overhead crane. He was quickly weighed and placed into a “shark box” — a long, narrow container filled with saltwater that limits the animal’s movement during veterinary procedures.

It takes a few added steps to ensure a Sandbar Shark can breathe while in a shark box. The Secret Reef’s other resident shark species, Sand Tiger Sharks, can breathe through a process called buccal pumping. Using muscles in their mouths, they can pump oxygenated water over their gills while remaining motionless, but Sandbar Sharks can’t do this.

Sandbar Sharks breathe through ram ventilation, which requires them to be in constant motion, swimming with their mouth open to pass water over their gills.

“If this was a normal fish, it would be a lot easier,” says Senior Aquarist Kyle McPheeters, “but because it’s a Sandbar Shark, we have to take special care.”

Through the entire process, an aquarist acted as a sort of anesthesiologist for the shark, using a pump to push highly oxygenated water – at oxygen concentrations of almost 200 percent – across its gills. That high oxygen concentration also acts as a sedative, helping keep the animal calm and relaxed.

With the shark secure and breathing comfortably, Dr. Keller got to work. He began by collecting several biopsies of the mass for laboratory analysis before removing the tissue entirely. Next, he performed “cryo-surgery” using a product similar to over-the-counter wart removers found at most pharmacies to cauterize the blood vessels and provide a clean surface for the shark’s skin to regrow.

“The way sharks heal, if there’s not any regrowth of the mass – which is still possible – you won’t even know we have done anything,” Keller says.

Though the nature of the mass is still unclear, the analysis of the biopsied samples by a histopathologist will determine whether the growth was bacterial, fungal, viral or – in the worst-case scenario – a malignant tumor.

At this point, all that can be done is to wait and see how the shark progresses, but both Keller and McPheeters are hopeful the surgery will ensure this shark lives a long, healthy life at the Aquarium.

“He’s still a young shark,” McPheeters says. “He’s about twelve or thirteen years old, and he’s a good resident, so we hope he has a long future here with us.”