If conservation scientists just had access to an “undo” button, a lot of time and energy — not to mention more than a few imperiled animals — could be spared.

When comparing the Herculean effort to restore an endangered species against safeguarding a healthy population from future decline, scientists have co-opted one of Benjamin Franklin’s witticisms: “An ounce of preservation is worth a pound of cure.”

More than a hundred years ago, the rush to fell timber led to rampant clearcutting of forests in Southern Appalachia. Robbed of soil-anchoring roots and the cooling shade of overhead branches, small upland streams began to warm and fill with runoff silt. These changes ultimately forced out the Southern Appalachian Brook Trout that relied on cool, oxygenated water to survive.

Decades later, the introduction of larger, more assertive Brown and Rainbow Trout into Appalachian waterways further strained Tennessee’s only native trout species. By the 1980s, the range for these beautiful fish — lovingly called “brookies” by their fans and would-be saviors — had been reduced to just 15 to 20 percent of its historical scope.

This year, the Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute marks the end of its first decade collaborating in the effort to return brookies to their native waterways. Despite the timespan of the Aquarium’s involvement, its scientists were relative late partners in the program, which was initiated by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) almost 40 years ago.

When it comes to the restoration of an imperiled species, stick-to-itiveness and hopeful ambition are crucial, says Dr. Anna George, the Aquarium’s vice president of conservation science and education.

“It’s all too easy for people concerned about protecting the environment to get gloomy when it seems like something wild is vanishing every day,” Dr. George says. “However, I’m grateful that through reintroduction programs like our work with Brook Trout, we can flip that story and bring something wild back.

“Humans are incredibly intelligent and resourceful, and when we work together in partnership, we really can make a difference and protect animals like the Brook Trout.”

We are confident we can save this species.

Sarah Kate Bailey, Reintroduction Biologist

Powerful partnerships

The Aquarium’s involvement in the restoration Southern Appalachian Brook Trout initially was undertaken as a kind of companion project to its long-standing restoration work with the Lake Sturgeon. Brook Trout also represented a particular challenge, scientifically, since populations in each stream tended to have distinct genetic signatures.

“That is a fun problem for a reintroduction program: How do you restore populations while still preserving those genetic identities?” Dr. George says. “It meant that we could work on best practices for a really challenging situation.”

Since 2012, the Aquarium’s involvement in Brook Trout restoration has been in concert with a variety of stakeholders, including TWRA, the U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Appalachian Chapter of Trout Unlimited.

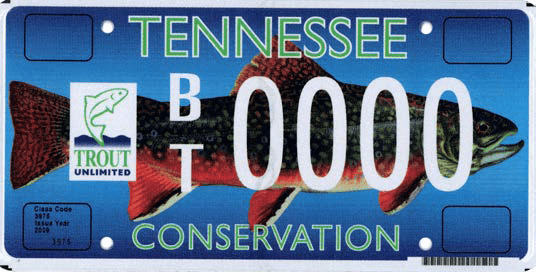

The propagation work is funded by Trout Unlimited through the sale of specialty Brook Trout vanity license plates. Beginning with an initial grant of $9,560 in 2013, this program has funneled more than $80,000 — an average of $8,900 a year — to fuel the Aquarium’s Brook Trout work over the last decade.

“From the start, the people who got the license plate going felt like the Tennessee Aquarium was a natural partner for us in our Brook Trout efforts,” says Steve Fry, the president of the Appalachian Chapter of Trout Unlimited. “We’re getting a little more mileage out of these releases thanks to this partnership, and we’re interested in doing more.”

Funding is only one component, if an important one, to restoring an animal to its native habitat. Bringing a species back from the brink is a complicated test of dedication and endurance. If it’s achievable, success can take years, if not decades, and involves close collaboration between wildlife managers, landowners, scientists, private citizens and other stakeholders to correct habitat mismanagement and reverse human-induced population decline.

When the Aquarium first weighed into the long-standing work to restore brookies, few Southern Appalachian Brook Trout had been raised in human care. Most propagation efforts had been conducted with individuals from Northeastern populations, which were determined to be genetically distinct from the Southern Appalachian strain.

Entering such a long-standing partnership, then, Aquarium conservation scientists’ early focus was on understanding the history of attempts to raise brookies before new approaches could be explored.

“Understanding more about past efforts at reintroduction and why they were less successful, and comparing the wild survival of individuals that were raised under different conditions were huge steps,” George says. “All of this has led to a very solid foundation for the program. It is nice to see how we have cleared some of these early hurdles and now are able to focus most of our attention on reintroduction instead of early research.”

Signs of success

The Aquarium’s propagation program for Southern Appalachian Brook Trout is a year-round affair, beginning each fall with the human-assisted spawning of adult brood stock. These fish are collected from genetically suitable wild populations and are induced to produce eggs (females) and milt (males) by lowering the water temperature of the systems in which they are cared for at the Conservation Institute’s freshwater field station.

After gently anesthetizing the fish and massaging their sides to collect eggs and milt, the eggs are fertilized and then disinfected. The eggs then are stored in special darkened “jars,” where they will hatch after about two months. As they grow and mature over the next five months, the young trout are relocated to progressively larger systems until they reach a releasable size of two to three inches.

“Being a small part of this long-term project feels important because of all the hard work that came before us and the hard work we will continue to do,” says Aquatic Conservation Biologist Dr. Bernie Kuhajda. “The propagation team enjoys caring for Brook Trout, but ultimately the goal is to have these fish out in the wild, fulfilling their role in the ecosystem.”

During their time in the Aquarium’s care, the young trout lack much of the distinctive coloration that makes their adult counterparts so sought after by anglers. Full grown Southern Appalachian Brook Trout are riotously beautiful, with red-orange bellies, white-edged fins and a splay of crimson and gold dots along their flanks.

To give the trout fry the best chance to survive, the Aquarium works in concert with TWRA and the U.S. Forest Service to monitor wild populations, restore habitat and identify suitable streams for future releases. Candidate waterways for reintroductions are protected by installed or natural barriers and are free of competitors and predators such as Rainbow or Brown Trout.

For the last several years, the Aquarium has released trout in streams winding through the Cherokee National Forest abutting the Tennessee-North Carolina border.

The forest is split into northern and southern sections by the sprawl of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. After a series of releases into streams in the northern Cherokee National Forest, reintroduction efforts in the past two years began targeting waterways in the Tellico River watershed in the forest’s southern half.

This southward shift was decided upon after welcome signs were found by TWRA that trout in previously stocked streams were beginning to reproduce on their own, an important measure of progress in the reintroduction effort.

“That is evidence that our restoration efforts are successful thus far,” says Reintroduction Biologist Sarah Kate Bailey. “We are confident we can save this species.”

The propagation team enjoys caring for Brook Trout, but ultimately the goal is to have these fish out in the wild, fulfilling their role in the ecosystem.

Dr. Bernie Kuhajda, Aquatic Conservation Biologist

Eyes forward

In late May, Bailey and other Aquarium biologists hiked alongside representatives from TWRA and members of Trout Unlimited to a release site on a pristine tributary of South Fork Citico Creek. There, they carefully navigated through a tangle of Mountain Laurel branches and over moss-slickened boulders looking for calmer pools and overhangs that offered ideal habitat for young brookies.

Throughout the day, the team released about 800 trout into the stream. Combined with an additional 300 juveniles destined for a second release, this year’s total “class” of brookies consisted of more than 1,130 individuals. With this latest series of reintroductions, the Aquarium and its partners in the last decade have released more than 4,000 of Tennessee’s native trout back into their ancestral waters.

Despite the milestone of ten years of participation in this restoration, Dr. George says few of the biologists involved were even aware of this year’s anniversary. Freshwater science, it turns out, is an eyes-forward kind of pursuit. Scientists undertaking marathon restorations don’t often pause to consider the timespan of their efforts, focusing instead on surmounting a steady stream of challenges with which they are confronted.

Nevertheless, she says, if the years— or even decades — of effort mean more Southeasterners will be able to see and appreciate the Southern Appalachian Brook Trout, administering the pound of cure will have been worth the effort.

“Obviously, the beauty of this species is part of why we want to conserve it,” George says. “But programs like this mean something much bigger than just the restoration of a single species.

“Whether it’s a small headwater stream or the Tennessee River, the waterways of the Southeast are full of life. It’s our goal at the Tennessee Aquarium to not only celebrate this life with the community around us, but also protect it so that future generations inherit and cherish the same animals that we have today.”