Recently, a senior aquarist checking in on off-exhibit systems at the Aquarium made an unexpected — and illuminating — discovery just in time for this year’s Shark Week celebration.

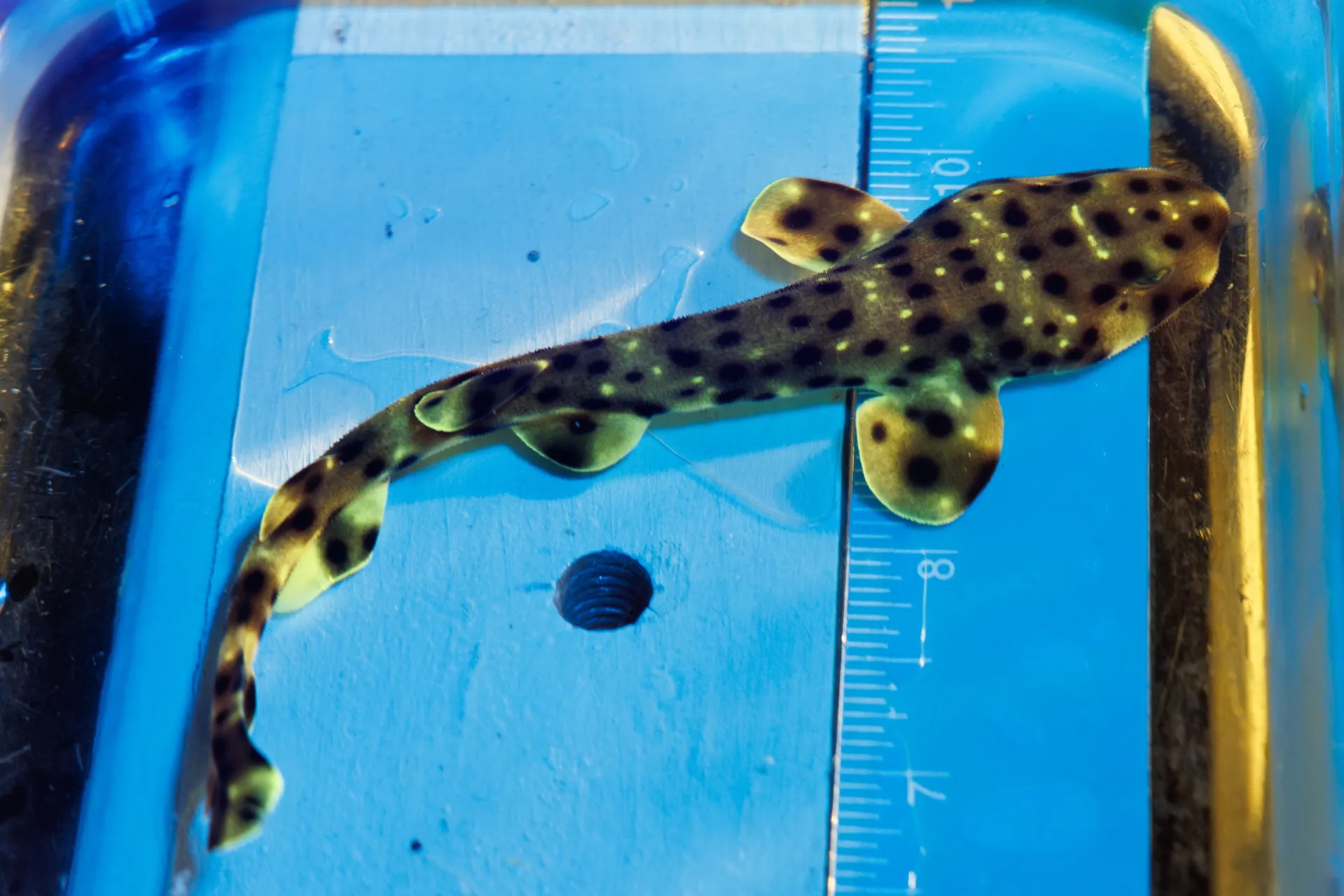

There, swimming alongside a pair of adults, was a baby Swell Shark. Colloquially known as “glow sharks,” this mottle-patterned species has developed a novel way to see others of its kind in the cold, dark depths off the Pacific coastline from California to Mexico.

“We call them that because they biofluoresce — they don’t make their own light, but they reflect light in a fluorescent manner,” says Senior Aquarist Kyle McPheeters, who first spotted the four-inch youngster.

“In the deeper parts of the ocean where they live, only the blue light is able to penetrate, so they are seeing in a blue light, but their eyes have a bit of a yellow lens on them,” McPheeters adds. “If you were to dive down to see them, they would look brown and would blend in really well in the dim light, but to each other, they would look like they were glowing.”

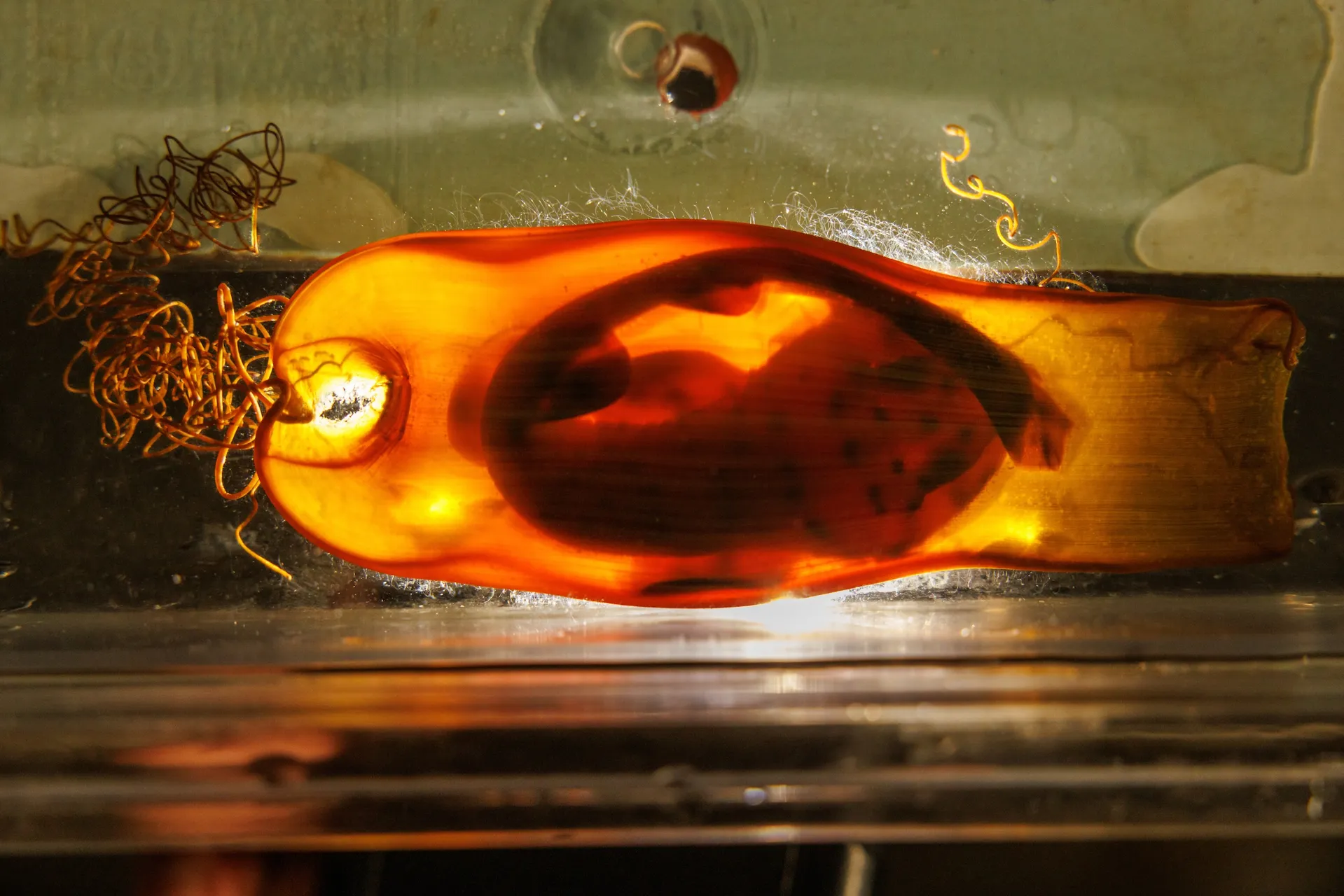

When we have eggs coming from the adults, that’s exciting … but to see that come full circle and come to fruition with a baby shark hatching from its egg is really exciting.

Senior Aquarist Kyle McPheeters

Using a handheld ultraviolet light and a pair of yellow glasses, McPheeters simulates what the sharks’ specially adapted eyes would see when looking at each other. Under the blue beam, the baby Swell Shark becomes hyper-visible, its body exuding a ghostly green luminance that starkly emphasizes its pattern of light and dark dots.

By the time it’s full-grown, this baby could reach up to three feet in length. The species’ unusual name references its defensive tactic of swallowing sea water to increase its body size to intimidate and deter would-be predators.

Hatching the Swell Shark was a first for McPheeters, a veteran caretaker of many different species of sharks and rays.

In addition to caring for Sandbar Sharks and Sand Tiger Sharks in the Aquarium’s 618,000-gallon Secret Reef exhibit, McPheeters tends to many sharks in the Stingray Bay touch experience, whose residents include Japanese and California Horn Sharks, Coral Catsharks and Epaulette Sharks. In his career, McPheeters has hatched and raised 90 Epaulettes, many of which are now exhibited at other Aquariums around the country, but this baby is his first Swell Shark.

The arrival of a baby shark is always worth celebrating, whether if it’s the first or the ninety-first, he says.

“When we have eggs coming from the adults, that’s exciting in itself, because it means we have a healthy environment where they feel safe reproducing,” McPheeters says. “But then to come in and see that come full circle and come to fruition with a baby shark hatching from its egg is really exciting.”

As of 2015, Swell Sharks were classified as “least concern,” the lowest threat level assigned by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). However, according to a 2021 study published in the journal Nature, shark populations have been in steep decline over the last 50 years due to human activity, mainly over-fishing. Since 1970, shark and ray populations have been reduced by 71 percent, according to the report.

By introducing sharks to hundreds of thousands of people every year, zoological facilities like the Tennessee Aquarium help debunk misconceptions of sharks as dangerous and highlight their ecological importance, McPheeters says.

“Sharks play a vital role in the ocean,” he says. “Just like land-based predators such as wolves and lions, they help to balance the food web and keep animal populations healthy by weeding out sick or injured individuals.”

For the time being, the Aquarium’s baby Swell Shark will remain with its parents and other juveniles in its off-exhibit home. Guests anxious for a jaw-some encounter during their visit to the Aquarium can see the many other species McPheeters cares for in the Secret Reef exhibit and Stingray Bay touch experience.

Another fin-tastic way to scratch your shark itch is by tuning into the Aquarium’s always-live Secret Reef web cam, which offers views of this colossal exhibit’s Sandbar Sharks and Sand Tiger Sharks as well as many other marine species. Check it out at tnaqua.org/live/secret-reef/