The need to seize teachable moments is so ingrained in every fiber of Julia Gregory’s being that her response to them is practically automatic. When natural phenomena come knocking, every nearby stump becomes a potential lectern, every garden a classroom, every mud hole a squelchy lab-in-waiting.

After a quarter-century as a senior educator at the Tennessee Aquarium, Gregory is retiring. By this point, however, teaching is so thoroughly hard-coded into her DNA that even the overwhelming crescendo of a chorus of cicadas during a farewell interview is seen as an opportunity rather than an intrusion.

“Cicadas … my favorite sound, the sound of summer,” she says, gesturing around to nearby trees reverberating with the insects’ shivering calls. “He’s out there — see the white spots? Those are his membranes. He doesn’t use his legs or his wings to make noise. He can vibrate those membranes to make that.”

At an arched eyebrow at this not-entirely-unexpected tangent, Gregory delivers not an apology but a shoulder shrug by way of explanation.

“I can’t help it! It’s wonderful; it’s magic,” she continues, mouth quirked at the crumbling edge of laughter. “I’m like the Lorax, but I don’t have to speak for things like Giraffes and Arapaima.

“With cicadas, everybody just goes, ‘Oh my gosh, they make so much noise!’ Well, they need to understand why they make so much noise and appreciate it and embrace it and enjoy it because life is too short not to.”

(Almost) Dr. Doolittle

Even before she joined the Aquarium in 1997 — because “I’m a sensible woman,” she laughs — Gregory was already well-seasoned at connecting the public with the natural world.

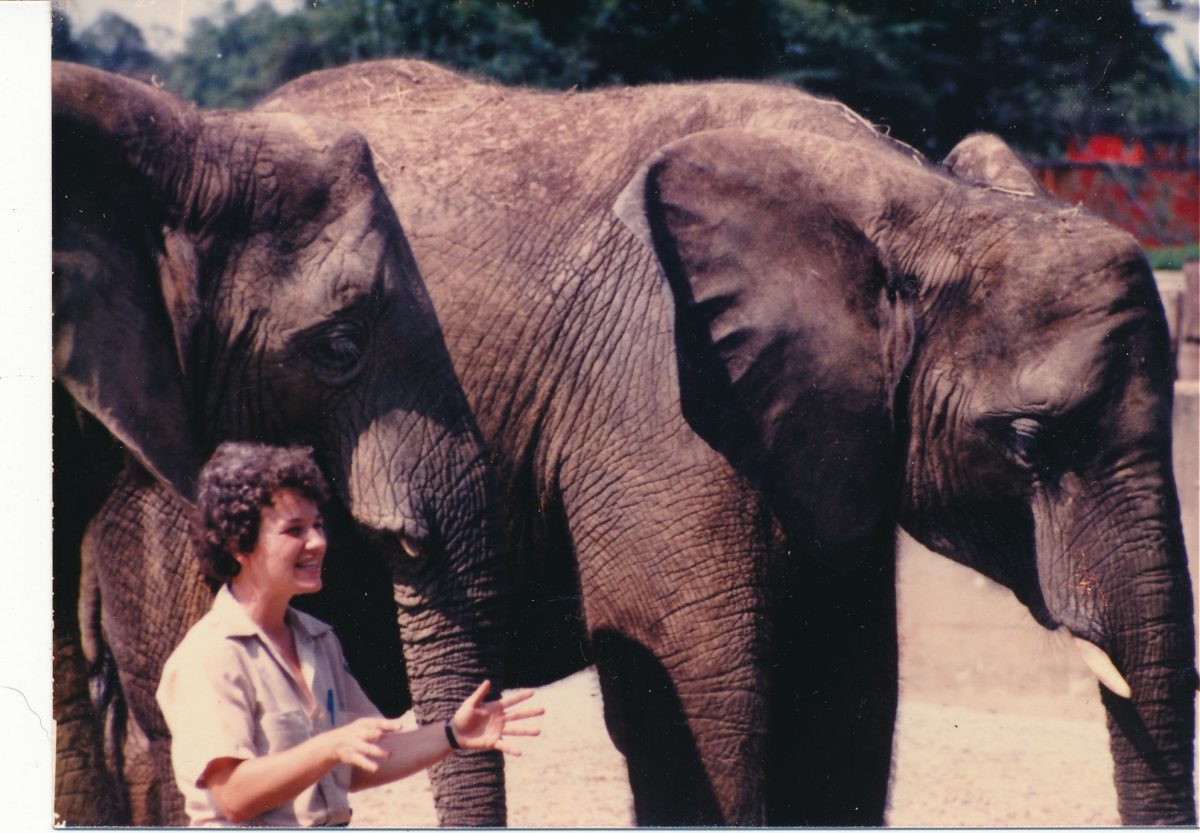

Prior to moving to the waterfront, she served as program director at the Chattanooga Nature Center, now Reflection Riding Arboretum & Nature Center. In the deeper recesses of her resume, she worked with native wildlife at the Athens’ Children’s Zoo in Athens, Georgia, and specialized in the care of Elephants and Sea Lions at the Virginia Zoo in Norfolk, Virginia.

For two years, she volunteered as a neonatal technician at the Center for the Propagation of Endangered Panamanian Species, where she tended to a pair of wild-born Black Howler Monkeys. In more recent years, she has served as a passionate and accomplished dog trainer (and past president) at the Obedience Club of Chattanooga.

Interacting with animals has always been more than just a professional obligation, though.

Fig. 1 Julia Gregory stands next to an Elephant while employed as a keeper at the Virginia Zoo (left). Gregory holds out her hand as a landing pad while training the Aquarium's Southern Flying Squirrels (right).

“Animals animate my world,” Gregory says. “They give me a reason to get up in the morning, to have someone to care for, to think about every day and to train.

“It doesn’t make me Dr. Dolittle — I can’t speak the animals’ language — but I can help the animal learn enough of my language, usually non-verbal, so that we can communicate and work as partners toward a common goal. That’s just thrilling to me.”

While speaking to countless visiting school groups, leading behind-the-scenes tours and hosting virtual programs, the Aquarium’s many Animal Ambassadors have served as Gregory’s furry and scaled teaching assistants.

A significant amount of her time has been spent working with these Animal Ambassadors, seeing to their care, earning their trust and training them to exhibit specific behaviors and adaptations, whether coaxing a Black Pine Snake to climb a tree, showing off a Blue-tongued Skink’s namesake oral appendage or — her personal favorite — encouraging a Flying Squirrel to soar from a raised platform onto her outstretched hand.

“Anybody alive today at the Tennessee Aquarium knows that the Flying Squirrels are my favorites,” she grins. “They weigh two ounces; they’re on many animals’ menu; they have to be constantly alert to danger and constantly alert to opportunities. In spite of all the predators trying to eat them, they have to figure out how to earn a living in a forest.

“I admire their ability to do that.”

Animals are more than just teaching props to Gregory; they are full-fledged coworkers and teammates. By bringing out a Sinaloan Milk Snake, a Cane Toad or an Axolotol, she can seize opportunities to connect visitors — many of them young — with the natural world in ways that inanimate objects simply couldn’t.

“That live animal is compelling to humans, and we want to use that charismatic appeal that animals still have for people,” Gregory says. “Somewhere deep down in inside, we know that we’re not really apart from nature, so when we see partners from nature, we want to connect with them.

“Our Animal Ambassadors help us to do that in ways that simply can’t be done with a computer program or a photograph or a stuffed animal.”

Fig. 2 Julia Gregory leads a group of children on a radio tag-tracking activity during a summer camp session. Gregory has spent most of her summers at the Aquarium leading camps for children of all ages.

The human animal

During the last 25 years, however, the species with which Gregory has had the most impact would have to be homo sapiens.

“One of the things I love about Julia is that she is a student of behavior,” says Dr. Anna George, the Aquarium’s vice president of conservation science and education. “I think she would say she’s a student of animal behavior, which is true, but that also translates to her being an excellent educator because she understands human behavior as well.

“She’s looking to take students of all ages, but largely kids, meet them where they are right now and move them a little bit further.”

Every summer, the Aquarium’s educators shepherd groups of 5- to 14-years old around the aquarium to classroom activities and on off-site adventures. It’s objectively hard work, albeit of the fulfilling kind, involving a lot of standing and walking in the heat while “surrounded by 20 young, inexperienced opinions … expressing those opinions, loudly at times,” Gregory says.

Nevertheless, she loved it.

“We want to feel that we have made a difference in somebody’s life, influenced someone to feel more kindly about the natural world, to value the natural world, to want to preserve the natural world,” Gregory says. “When it came to summer camp, it felt like maybe, just maybe, this was our very best opportunity to reach that goal, to have the same group of young people for five whole days straight, to show them and involve them and hook them.”

But even when she couldn’t get five days in a row, Gregory would happily take one day a month.

Started in 1999, the Aquarium’s Bug Club program invited participants ages 5-12, along with their families, on excursions designed to help them look with greater favor and interest on the world of spiders, insects and other invertebrates.

During her tenure with Bug Club and its successor, Nature Nuts, Gregory worked alongside long-time co-educator and self-described “faithful helper,” Bill Hailey, the Aquarium’s recently retired education outreach coordinator.

Whether it was impromptu dips in mudholes or an unexpectedly harrowing attempt to relocate a colony of Bumblebees, Hailey remembers Gregory most for her deep knowledge of and enthusiasm for the natural world.

“She has a great ability to connect with her audience, she knows and loves her subjects and the animals she worked with and she is PREPARED,” Hailey says. “Julia is one of those characters that sticks with you. Those kids never had a lack of interaction with nature.”

Always moving forward

Throughout her time at the Aquarium, Gregory never ceased pursuing ways to broaden her knowledge of the natural world and to learn new methods to convey that to the public.

In addition to summer camps and Bug Club, she facilitated overnight programs with the Girl Scouts and was a member of the National Network of Ocean and Climate Change Interpreters. She has been trained to facilitate a range of conservation and environmental education programs through the Project WET Foundation and the Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies.

Fig. 3 Senior Educator Julia Gregory demonstrates proper touching technique in Stingray Bay to summer campers.

Fig. 4 In the wake of the pandemic, Aquarium educators like Julia Gregory had to adjust their methods to reach students who couldn't visit in person, including leading virtual classroom programs (left). In her years at the Aquarium, Gregory constantly found ways to share and expand upon her expertise, including recurring programs like the Bug Club (right).

Even in the months leading up to her retirement, Gregory has been pursuing a program focused on improving education evaluation at the Aquarium. That dedication to her profession in the waning days of her career speaks volumes, Dr. George says.

“That shows me who she truly is as a person, someone who continually challenges herself, is constantly curious about the world and is constantly hoping to inspire others to do the same thing,” George says. “Julia has shown us how important it is to keep learning throughout your life, whether you’re a four-year-old playing in a mud puddle or someone who is approaching retirement. It’s that excitement, that curiosity and that passion for science that Julia has really imprinted on our department.”

Never one to pass up a chance to deepen her understanding of the world around her, Gregory intends to fill her days ahead — at least in part — with contemplative, directed observation of natural phenomena from a dedicated “sit spot” on her rural property in McDonald, Tennessee.

A Gregory-ian take on Henry David Thoreau’s Walden Pond, perhaps?

“I think he worked too hard,” she laughs. “I’m just going to sit.”

As the nearby cicadas continue issuing increasingly voluminous catcalls at each other, Gregory pauses as she considers the impact she’s had during her time at the Aquarium. Over the years, she and her teammates reached many minds and helped many people become more receptive to the natural world. They may have missed a few, she says, but their efforts were never wasted.

“We won’t win them all, but we want to win every single one we can,” she says. “It doesn’t matter what my students became in the machinery of the world. If they’re just taking that understanding of the importance of the natural world with them, then I’ve achieved my goal.”

Fig. 5 Senior Educator Julia Gregory holds a snake at the Tennessee Aquarium's 30th anniversary VIP celebration event.