When it comes to survival, the freshwater mussel’s approach to reproduction could give even Steven King a case of the shivers.

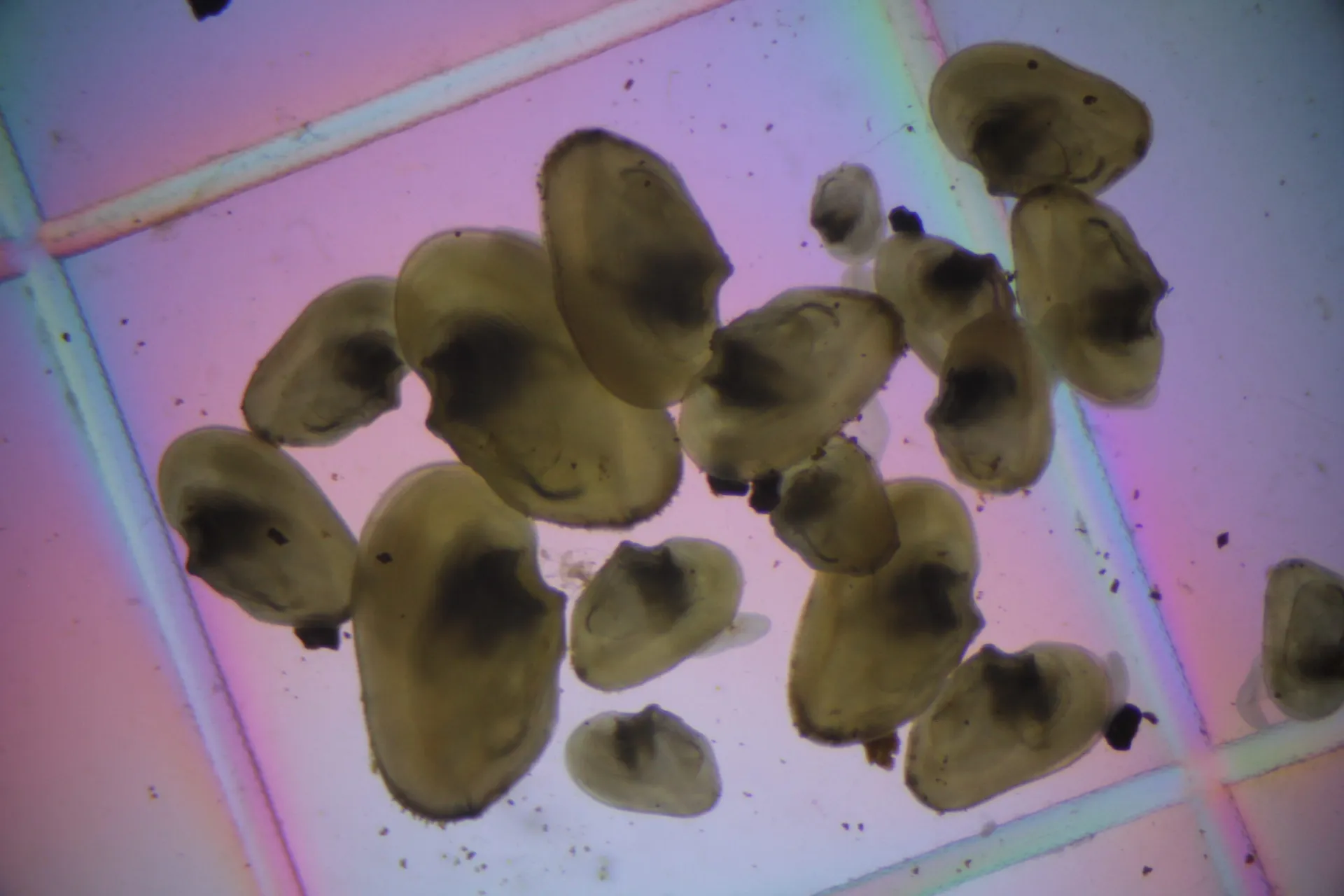

When it’s time for their microscopic larvae to continue developing, female mussels must parasitically infect a specific host species of fish with their offspring.

Some mussels eject their larvae into the water hoping they’ll passively infect nearby fishes, but others take a more novel — some might say “cunning” — approach.

There are mussel species whose larvae are in packets disguised as small fish or insects, which larger fish attempt to eat, infecting themselves in the process. Other mussels have fleshy mantles that resemble prey desirable to their host fish species. When a hungry fish hones in on this “easy” meal, the mussel expels its larvae at the peckish diner or clamps its shell around it, restraining it and directly infecting its skin, fins and gills.

Terrifying as these Alien-like sneak attacks sound, infected fish aren’t harmed by their hitchhiking guests, who eventually are covered over by tissue and have little impact on the fish’s health or nutrition. After a few weeks, the juvenile mussels are ready to drop off, sometimes having been carried upstream to new locations they otherwise couldn’t have reached.

Recently, the Tennessee Aquarium joined forces with Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency-managed Cumberland River Aquatic Center in Gallatin, Tennessee to lend a helping fin to the host-less offspring of four endangered species of native bivalves.

“They reached out to the Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute because we are well-known for raising fishes,” says Aquarium Science Programs Manager Dr. Bernie Kuhajda. “They were hoping we could propagate some fish for them to use in raising their mussels.”

Under pristine blue skies, a team of freshwater specialists from the Conservation Institute waded into South Chickamauga Creek to bring back about two dozen Common Logperch to their propagation facility near downtown Chattanooga. Less than an hour later, they more than met their quota, the fine-meshed seine net having collected about 30 Logperch in addition to a host of crayfish, insect nymphs and wriggling masses of Mountain Madtoms, Warpaint Shiners, Stonerollers and other fish species.

“That was definitely the easiest collecting trip I’ve ever been on. It doesn’t get much better than that,” says Aquarium Reintroduction Biologist Meredith Harris. “It’s really encouraging to have a stream that has such a healthy level of biodiversity like South Chickamauga Creek right here in our backyard.”

The sleek, tiger-striped, green and gold Common Logperch can reach about seven inches in length and — as its name suggests — is widespread from Ontario to Alabama. Although it isn’t considered imperiled, the Logperch’s offspring will be vital to efforts to raise endangered Dromedary Pearlymussels, Cracking Pearlymussels, Fanshells and Snuffbox Mussels, all of which can be found in the Tennessee and Cumberland River watersheds.

Once infected by mussel larvae, fish develop resistance to future infections. As a result, individuals generally only play host to a single generation of mollusks.

“You can’t just go out and catch fish and bring them in because if they’ve already been infected, it won’t work as well,” Kuhajda says. “And we don’t have any way to test the fish to see if they’ve already built up an immunity to being infected.”

You can’t just go out and catch fish and bring them in because if they’ve already been infected

Early next year, the offspring of the collected Logperch should be large enough to be shipped to the Cumberland River Aquatic Center. By only sending fish that were hatched and raised at the Aquarium’s freshwater science center, each one will be accustomed to the environment of a hatchery and guaranteed to have a clean infection record.

That should make them the best possible hosts for the mussels, Kuhajda says.

“This way, the Aquatic Center can infect them with larval mussels, and they won’t get overly stressed or potentially reject them,” he says. “They’ll be relatively happy Logperch, even though they have little mussels attached to them.”

The partnership between the Aquatic Center and the Aquarium will continue for two years with new Logperch being sent over once previous groups of fish have been infected and their bivalve hangers-on detached.

“Recovery of threatened and endangered species requires collaborative conservation efforts, says Dr. Dan Hua, Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Senior Scientist at the Cumberland River Aquatic Center. The fish host is critical in mussel propagation and restoration. Cooperating with our partners, such as the Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute, we will successfully keep the wheel running in this conservation journey.”

“We’re all in this together. It’s going to take everybody’s effort to recover these animals,” Harris says. “We’ve got a lot more work to do, but we now have the fish and that’s an important first step.”

Tennessee waterways are host to more than 120 species of mussels. More than 90 percent of the continent’s mussels can be found in waterways within 500-miles of Chattanooga. Many mussels can live for decades, during which time they are constantly siphoning food from the water flowing over and past them.

“As they do that, they filter out contaminants,” Kuhajda says. “If we want water that’s safe to drink, to swim in and to fish in, mussels are an integral part of that system that gives us clean water.”

mussels are an integral part of that system that gives us clean water.