Shell Creek is pretty much a picture-perfect Appalachian mountain stream.

From headwaters within a stone’s throw of the Tennessee-North Carolina border, it descends through the Cherokee National Forest in a burbling dance over and around boulders coated in carpet-thick layers of green moss.

Shell Creek is an undeniably beautiful waterway rife with stairsteps of terraced falls separated by clear, slower-moving pools. Even more importantly to biologists, however, the creek’s upper reaches are largely free of non-native Rainbow and Brown Trout thanks to a natural barrier preventing their movement upstream.

The absence of competition for resources makes this stretch of the Shell an ideal location for the next chapter in the restoration of the Southern Appalachian Brook Trout to its historic range.

Over the course of three years, Brook Trout restoration efforts were focused at Little Stony Creek, another cold-water stream about ten miles north of Shell Creek. In the last year, however, biologists were excited to find naturally spawned fish in Little Stony, a clear indication that restocking had been successful.

“The fish we introduced there are now producing enough on their own that we don’t have to help them anymore,” say Tennessee Aquarium Reintroduction Biologist Meredith Harris. “This year feels like starting a new chapter. Now, it’s on to the next location.”

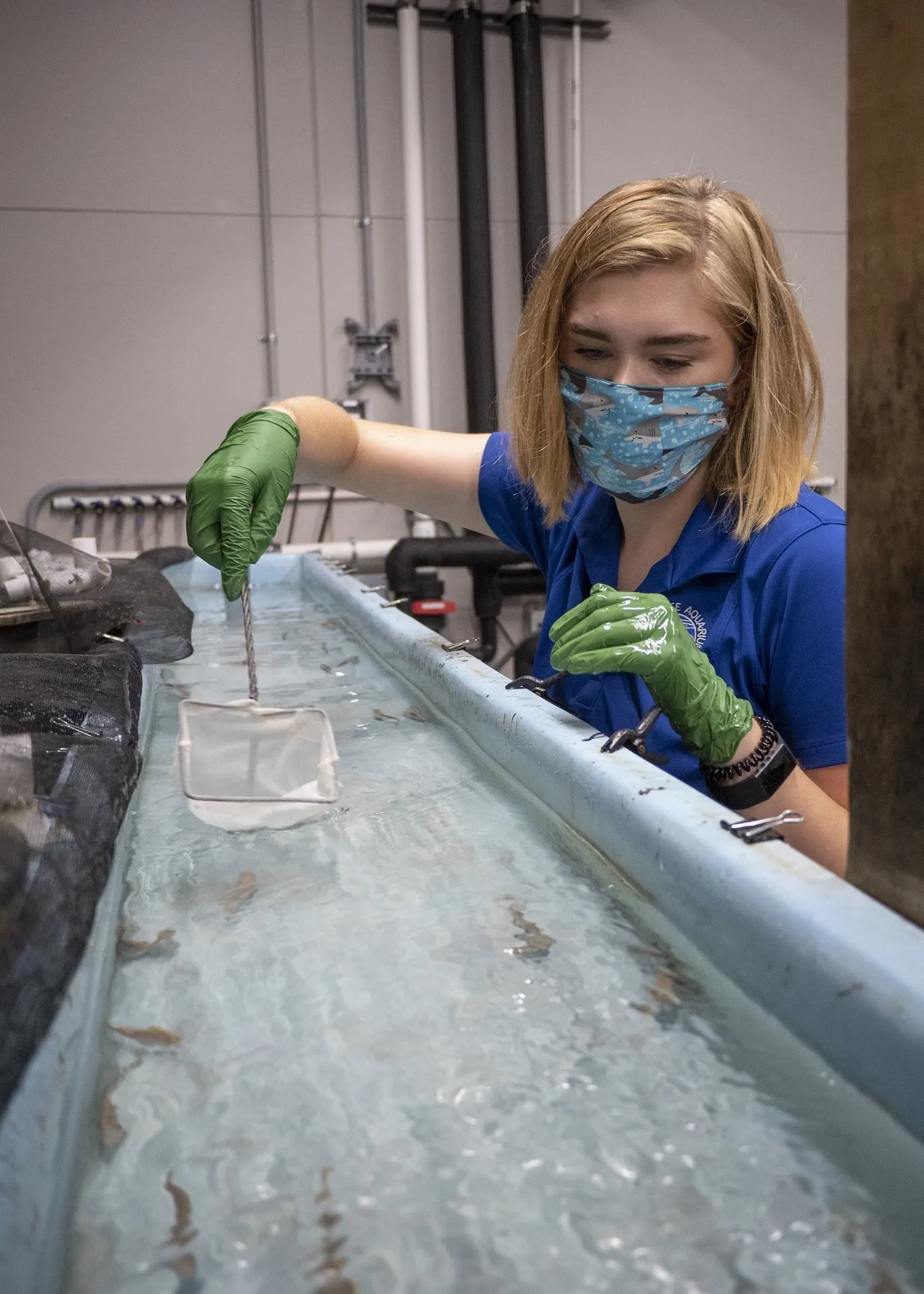

The first stocking effort at Shell Creek began before dawn as Harris and Reintroduction Assistant Anna Quintrell collected more than 400 juvenile Brook Trout from hatchery systems at the Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute’s freshwater science center near downtown Chattanooga.

After getting the fish ready for a road trip in oxygenated bags cooled by ice packs, Harris and Quintrell drove more than 250 miles to reach a stretch of Shell Creek bordered by a meadow of waist-high grass off a steep, switchback gravel road.

Once on site, Harris and Quintrell joined representatives from Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, U.S. Forest Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. While the Brook Troutacclimated to the water of their new home, the reintroduction team discussed where and how best to release their charges into the brisk, 58-degree current.

“The Brook Trout is the native species here in the Appalachians, and we want to get those back into our streams,” says Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Streams and Rivers Biologist Sally Petre. “It’s nice to close the door a little bit on Little Stony Creek. Now, we can put effort into spawning and rearing fish to stock Shell Creek and hopefully see more production here, too.”

This year feels like starting a new chapter. Now, it’s on to the next location.

Brook Trout — or “Brookies,” as they’re affectionately known to anglers and other ichthyophiles — used to thrive in places like Shell Creek. Beginning in the 1920s, however, the introduction of non-native species, clear-cutting of forests and alterations to streambeds saw Brook Trout species reduced to 15 percent of its historic range in the Southeastern United States.

In the wild, Brook Trout are wide-ranging and can be found from the Southern Appalachians into Canada. However, the southern strain of Brook Trout — the Southern Appalachian Brook Trout — is genetically distinct from northern populations.

In the 1980s, TWRA began what has become a decades-long quest to restore Brookies to their native southern waterways. In 2012, the Aquarium leant its expertise to this effort by spawning, hatching and raising juveniles for release back into the wild.

With the release of this year’s class of propagated fish, the restocking effort has seen more than 3,000 Brook Trout returned to their native waters.

The propagation process is a time-intensive affair, which begins in late October with the spawning and fertilization of eggs from brood stock at the Conservation Institute. The daily care of these juvenile fish is funded by the Appalachian Chapter of Trout Unlimited through the sale of special Brook Trout license plates.

“We want to have these streams in the best condition we can have them in for future generations,” says Trout Unlimited Appalachian Chapter President Steve Fry. “Brook Trout belong there. We’re at the southern end of their range, so this is where it’s most important to try to take care of them.”

Despite eight months of work rearing these juvenile — or “fingerling” — trout to a releasable size, their reintroduction into Shell Creek is over in less than two hours.

Team members worked their way up and downstream over slick rocks and through patches of stinging nettles while carrying dip nets and buckets. Stopping occasionally along the waterway, team members carefully deposited fish, a few at a time, into calm pools and in the shadowy lee of overhanging boulders.

When reintroduced, these fingerlings are mostly pale silver — the only suggestion of their future brilliance being a faint reddening of their tail and pectoral fins. When they are full grown, Brook Trout are a riot of color, with white-edged fins and sides that brighten from olive to crimson with gold and red speckling.

Despite the speed with which the reintroduction took place, the conservationists laughed and celebrated the moment when their buckets emptied. For those involved in such long-term conservation programs, the effort can sometimes feel like a battle of attrition, years of effort with few noteworthy signs of forward progress. Seeing successful wild breeding of reintroduced fish is a rare, special moment, Harris says.

“That’s the end game for us,” she says. “To put them back into the water and know that they’re swimming in the stream where they belong is just the best feeling in the world.

“The little fish we put in today are kind of like the pioneers of this stream. They’ll be the first Brook Trout to swim here since they disappeared however many decades ago. That’s really exciting.”

The little fish we put in today are kind of like the pioneers of this stream.